Asia Alfasi’ ‘Extraordinary Tales’: Bringing Together Libya, Scotland, and Manga

By Valentina Viene

In a world of opposing ideologies and intense scrutiny, critically thinking individuals must often migrate to an imaginary world to express their ideas. For writers with a message, fiction offers that free space where they can create their own scenarios and explore their own ideas. While new genres like science fiction are gaining increasing visibility, Arab graphic novels and comics remain relatively unknown to the Anglophone readership, although comics are familiar to both audiences. As a genre, comics have the advantage of facilitating communication, thanks to the cross-cultural overlaps.

Comics and cartoons are by no means new to the Arab world. The “Sindibad” series for children were already popular in 1950’s Egypt, and the Middle East has long used cartoons as an invective against oppression. Now, these traditions are coming to public attention in the West. For instance, some of these cartoons and cartoonists were showcased at the Shubbak Festival in London last July.

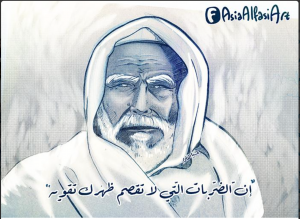

One of the emerging voices in the world of comics is Asia Alfasi, a young but prolific artist based in Birmingham who describes herself as a “Muslim Libyan Arab British graphic novelist.” Alfasi’s story of how she came to manga cartoons is quite unique. At the age of eight she moved from Tripoli, Libya, where she was born, to Glasgow, Scotland. At school, she struggled at establishing relationships with her peers. The cultural distance was a great obstacle for her, and Alfasi was bullied.

Outside of school hours, she would watch manga cartoons and draw. Then something happened that changed her life. Her classmates discovered that she could draw manga, and draw well, too. She suddenly became popular and children started respecting her. She not only managed to “subdue a monster,” to use Alfasi’s own words, and pull down those walls of fear, but she felt that her drawings could influence the world.

Her intimate relationship with drawing has resulted in recognition. Her work was included in the Mammoth Book of Best New Manga in 2006, alongside artists of international reputation. “The non-savvy non-commuter” was displayed on the walls of the Piccadilly Circus tube station on its 100th anniversary in 2006, a year after London was left in shock by the 7/7 terrorist attack. It talks about a Muslim girl from Scotland, Ewa, who uses the London underground after a long time. She very quickly becomes a commuter’s nightmare because of her clumsiness. She joins a childhood friend, Yasmin, who in seven years of living in London has dramatically changed in looks, such that Ewa does not recognize her. A discussion between the two follows, where Ewa expresses her astonishment at Yasmin’s transformation. Yasmin calls it “tactical re-branding” to adapt to her new environment. Ewa disagrees with her and asks her friend to look at the people in the underground and notice how their differences come together to make a beautiful symphony. And the fact that Ewa wears a hijab means that her identity is represented in the crowd.

While Alfasi’s first pieces were focused on her personal experiences, the Arab Spring has taken her work in different directions. She returned to visit Libya in January 2011, but with the uprising against Gaddafi, she ended up staying for a year or more. During that period, she encountered first-hand the horrors of war and the victims of the Gaddafi era.

When she decided to write about Libya, her parents tried to dissuade her, since two of her uncles had already been imprisoned then killed for being too vocal under Gaddafi. For a while, she left her new project, but then felt compelled to recount those stories, which, after her stay in Libya, had found new meaning. These stories inspired Alfasi to write her first semi-autobiographical novel which is soon to be published by Bloomsbury USA. Alfasi harnesses the fact that she is an in-betweener. She has realized that she can talk about Libya and Scotland from an insider’s perspective and “give each culture a chance to look at themselves through the eyes of a person who has lived there first as a national and then almost as a newcomer.”

Alfasi’s message is a message of optimism, and that words can change the world. If manga helped her gain acceptance in her school, surely, she suggests, this will contribute to a reduction in the distance between the West and other cultures.

“The moment,” she says, “you step away from stupid generalizations and predictable stereotyping, you suddenly enter the realm of intriguing stories that will add and benefit and teach you and enlighten people.”

In “Hijabstrip,” a white girl is caught by surprise when she first enters her Muslim friend’s bedroom. She has Bruce Lee posters hanging on her walls. She opens her friend’s wardrobe and discovers that she has some really fancy dresses. Her eyes almost pop out when she realizes that not only is her friend not covering her head with a scarf, but that her hair is blue! The Muslim girl teaches her friend not to judge by appearances. She also wears a Pikachu pyjama and takes part in Karate tournaments.

The artist describes her work as “a cultural blend of extraordinary tales.” Her work is truly extraordinary: she is among the the first Arab artists to have introduced Muslim characters in the manga world, as well as legends and myths of which the Libyan culture is so replete. She also has sense of humour, which makes her stories a pleasure to read. Her re-adaptation of Juha’s traditional tales to comics, for example, is brilliant and can be read on her Facebook page, both in Arabic and English.

Currently, she is also working on a project to turn a theatrical piece, “Looking for yoghurt,” into a graphic novel. She is writing a third story, “The Adventures of Joseph and Jasmine” which should be published soon. Because of her bilingualism, her work is accessible to a great variety of readers, which will no doubt bring her a wide audience.

This article was cross posted from Arablit here.

Valentina Viene is a translator from Arabic into English and Italian and a literary scout focusing on contemporary Arabic literature. A graduate of the Orientale, Naples, she has translated a number of Arab authors and her articles have appeared in Italian academic journals and blogs. She has lived in and around the MENA region for several years.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of MENA etc.