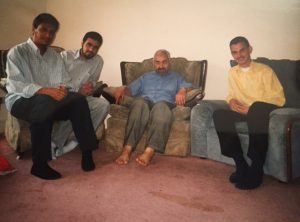

Fathi Warfali: A Democrat who Sought Martyrdom in the Fields of Afghanistan.

Mr. Fathi Warfali is one of Libya’s earliest and youngest political activists and hails from a pedigreed religious and scholarly family from Bani Walid. At sixteen he joined the nascent Islamic movement in Libya. Despite being a committed democrat he decided like many of his generation to join the Mujahideen to fight the Soviets in Afghanistan. Several times the young Warfali tried to join them but returned having failed to make it over as the Pakistani authorities made it harder for Arabs to travel to Afghanistan.

To Mr. Warfali, Afghanistan was the modern equivalent of what Syria is for young Muslim men, a bleeding open wound. He followed events in Afghanistan devotedly. He returned to Libya in 1993 having failed once more to get to Afghanistan and participated in the Islamist political agitation of the 90s. He was imprisoned, and was later forced into hiding after 1995 when a failed coup led to arrests and rounding up of suspected opposition members. He hid in the same house for two years trying to obtain forged passports, “I lived like a prisoner”, he recalls, “sometimes the secret police came and there was only a door between them and me.” In the end he managed to get to Switzerland where he sought political asylum.

When the insurrection broke out in 2011 in Libya, he joined the revolutionaries and fought his way to Tripoli counting Mahdi al-Harati and the likes of Abdel Hakim Belhadj as his comrades in arms. Mr. Warfali then became member of the higher Tripoli security council rubbing shoulders with politicos that now sit in the Rixos hotel. However instead of immersing himself in the messy political atmosphere of Tripoli, Mr. Warfali shunned political life and decided to concentrate on bringing Libyan human rights violators to justice from both sides of the divide; the winners and the losers. It is probably for this reason that no one, including the British security services, knows quite what to make of him – after all it is not often you come across a democrat that once sought martyrdom in the fields of Afghanistan. Arguably, it is precisely because Mr. Warfali occupies this ambiguous position which makes his insights so valuable.

Mr. Warfali knows very well that the West has its own interests to protect but he believes that those interests converge with the interests of Libya; Libya has oil but does not have the technology to extract and refine it and so he concludes, “we need each other”. In order for those interests to be satisfied it is imperative that Libya is stabilised, and he believes this stabilisation needs a multi-pronged approach. Firstly, Britain, Italy and the United States, the main players in Libya, must support the Libyan people as a whole without taking sides that would contribute to their own security. Secondly, whilst he believes that ISIS is not as big a problem as the West maintains, Libyans have paid a heavy price for fighting them and that needs to be respected, recognised and supported. Finally, defeating ISIS in Sirte is only a short term solution, in order for them not to make a resurgence and rely on the support of the defeated tribes that fought on the side of Gaddafi, those tribes need to be placated.

“ISIS has taken advantage of the enmity of the defeated tribes after the fall of the previous regime… there was no security, no wealth, no growth. Cities like Sirte, Bani Walid, Sabha were neglected. It allowed ISIS to fill the vacuum. Now we need to return to reconstruction and growth, we need internal dialogue and a military and security presence in those areas so terrorist organisations do not return.”

Ultimately Mr. Warfali believes terrorism is a mindset and must be fought with ideas and the participation of the people.

Similarly to solve the migration crisis, yet again it is within the West’s best interest to support Libya. He considers it unrealistic to expect Libyans to solve the problem on their own. The routes that smugglers, migrants and refugees use are trade routes that has been utilised for centuries and cannot be shut down just like that. In fact, the profits gained from mass migration is such that there are rumours that the Italian Camorra and the Sicilian Mafia have got involved. Considering the scale of profits that are being made, it is not surprising that there are a lot of interested parties who would want these routes to remain open. Militias, politicians and transnational actors, amongst others, are all kept afloat by the ‘taxes’ and ‘bungs’ from the mass migration movement of goods and people.

Mr. Warfali suggests that the solution for the migration crisis must be comprehensive:

“even the Americans and the Europeans with all their wealth and might can not solve it… we need to support the security organisations that are present in Libya… the person who is trying to fight this on a salary of one thousand dinars will definitely let you through if he gets hundred thousand dinars. Mass migration is a regional problem and regional countries should play its role…I met with the commander of the 3rd battalion who told me that ‘the European Community and especially the Italians visited me. They promised us this and that but so far nothing has come’. There are groups in Europe that benefit from this. We are talking about millions sustaining armed militias and terrorist groups. The international community need to combat this completely…of course Libya does have a role. But it is crucial that Libyan organisations that fight migration are not caught up in the political struggles of Libya and stay neutral.”

But could the West work within a political landscape where Islamists and Liberals are seemingly at odds with each other? Mr. Warfali is an unashamed Islamist and part of the Libyan political landscape. He makes no apologies for that. “Under Gaddafi” he says, “we paid the price, we were killed, imprisoned and tortured…yet it was the Islamists who organised Parliament… and no election fraud was recorded.” But though he recognises the contribution of the Islamists in Libya, he is also highly critical of them. They like everyone else “went after power, partisanship, took part in corruption, illegal arrests, and torture – they became like the previous regime.” He believes that part of the problem was that Islamists never developed their own local political tradition but imported ideas from outside and as a result produced a tradition that was not “suitable to its habitat”. The Islamists failed in Libya because they didn’t understand the Post-Gaddafi situation and then they became “the enemy of the people.”

Whilst Mr. Warfali is highly critical of the Islamists he doesn’t believe that there is the same clash between Islamists and Liberals that exists in Egypt for instance. In his view, the West must understand that the political climate is far more nuanced and perhaps even healthier than that in Egypt. In Libya, Gaddafi monopolised the apparatus of power, security and wealth, after his fall “various groups” he says “took control of these portfolios.” “Libyans believe,” he continues, “that to secure power is to secure wealth and to secure both is to have a strong arms.” In other words, in Libya it is not necessarily a matter of political ideology. Mr. Warfali offers the following example to back up his point: “the Justice and Construction Party is affiliated to the Muslim Brotherhood and are supported by the Misratan tribes who are liberals but they support Islamists because they are financially supported by them.” Similarly he points to the Salafists who “fight with Haftar even though he is secular.” These so-called ideological clashes are “all just appearances.” In the end, Mr. Warfali believes, that Libya is afflicted by competition for resources and that at base we are dealing with the same issues that have affected most human societies since time immemorial.

In spite, of the chaos caused by the power vacuum, Mr. Warfali is optimistic about Libya’s political future. He believes that if Britain or Italy had twenty five million pieces of heavy to mid-range weapons in each home there would be chaos and yet in Libya crime levels are still relatively low. Libya has freedom of expression, free press and so much more he insists.

But still is there a solution for Libya’s current crisis? Many have pointed to General Haftar’s authoritarian rule as a possible solution. Certainly Gen. Haftar cannot be ignored in Libya’s political landscape, and that in someways he is perceived as representing US interests in the region. And so groups are making deals with him, even though he may be reviled and viewed as a counter-revolutionary and a throw back to the Gaddafi era. Whilst it might be a question of Realpolitik, Mr. Warfali doesn’t place much faith in Haftar’s ability to shore up the problems in Libya singlehandedly, for as he says “not one party can resolve the issues in Libya, it only requires one party mess everything up.” Currently what we are witnessing in Libya is Haftar demonstrating his ability to do that.

The one thing that remains a constant in Mr. Warfali’s political vision is that the solution lies in democracy. “It is the only way,” he says, “to have the safe transferral of power without violence”.

These ideas very much echo Mr. Rachid Ghannouchi’s political philosophy. The Islamist thinker’s Ennahda party also believes that democracy can be used as a political mechanism to remove tyrants and corrupt rulers without resorting to bloodshed and civil strife; this has always been a problem that Islamic history has grappled with since its inception. Mr. Warfali knows Mr. Ghannouchi and it is highly likely that he would have been influenced by Mr Ghannouchi’s ideas.

Even though Warfali’s ideas are similar to other North African Islamist parties who regard their Islamic political tradition to be indigenous and fluid, from some corners of the political spectrum Mr. Warfali is seen as a liberal sell out. He is regarded as someone who has chosen secularism over the rule of God. But Mr. Warfali though is resolutely illiberal. If Libyan parliament had to vote for ‘Gay marriage’ to take an example, he would vote against it. Nevertheless, if Libyans voted for its legalisation he would accept a decision even if it contradicted the Shariah. But he adds, “he would hate it in his heart”. In any case he points out that there are many things that Libyans won’t accept and democratic countries are safeguarded by the constitution and “Libyans are free to shape a constitution that won’t contradict their religious beliefs”. So Western interest may coincide with Libyan interests but it does not automatically mean that Libyan democrats like Mr. Warfali are simply, “brown Westerners” parroting the theories of the West without any ideas of their own. Mr. Warfali’s confidence in his ideas are perhaps indicative of the emergence of an Islamist discourse in the region that is more comfortable with its relationship with democracy.