Musa al-Qarni on the Afghan Jihad

The Afghan Jihad: An Annotated Interview with Musa al-Qarni about Abdullah Azzam and Ahmed Shah Massoud and the tension with the ‘Afghan Arabs’

In my research into the Arab Afghans I came across this interview which I thought I would share here. This article is important because it shows how nuanced the environment was in Afghanistan during the Soviet invasion.

The Interview has relevance to the following:

- Role of Ulama (or religious scholars), in inciting, educating and propagating the Jihad in Afghanistan

- Similarities between foreign fighters going to Syria to cleanse themselves after living ‘dissolute lives’

- The role of intelligence agencies

- The ‘Trial of Massoud’ which reveals the internal politicking of the Arabs and Ahmed Shah Massoud. The account have been independently confirmed to me by Abdullah Anas himself. This could have been the seeds for Ahmed Shah Massoud’s assassination two days before 9/11.

- Sheikh Abdullah Azzam, a figure claimed by al-Qaeda as one of their own, considered Ahmed Shah Massoud a hero.

- Role of Gulbuddin Hekmatyar and other Afghan leaders in the Afghan Jihad.

Biography of Musa al-Qarni

Al-Qarni was born in Bish in Jazan province Saudi Arabia, in 1954. He obtained his doctoral degree in Usool al-Fiqh, Principles of Islamic Jurisprudence from Umm al-Qurra University in Saudi Arabia. He held various professorships and headships related to Islamic Jurisprudence at various Islamic academic institutions. He was also a President of the Islamic University in Peshawar. Al-Qarni too travelled to Afghanistan early and became heavily involved in the Afghan Jihad in particular, relief work and educational activities. He came in contact with Afghan leaders as well as Abdullah Azzam, Abdel Majid al-Zindani, Osama bin Laden and others.

Al-Dhiyab notes that al-Qarni was someone who raised or incited Jihad. He was politically shrewd enough to keep everyone on side; he was friend of both Ahmed Shah Massoud, Osama bin Laden and a group known as the ‘Takfiris’ led by the likes of Dr. al-Zawahiri. This of course, brought him a fair share of problems after 9/11 when the political climate had changed. He was dubbed a ‘mufti’ or ‘judge’ to Bin Laden, even though he was an opponent of Mullah Omar’s Taliban and yet he was an ardent defender of Ahmed Shah Massoud from charges of apostasy. In equal measure, he was also considered a reformer and belongs to the Jeddah Reformist Group. This ambiguity coupled with his political activities, in particular noting the contradictions in KSA’s policies in the Afghan Jihad, led to him being sentenced to 20 years and receiving a 20 year travel ban.

Below is the Interview between al-Dhiyabi and al-Qarni with my commentary in Italics I have added hyperlinks to important figures mentioned in the interview. This interview was conducted by Jamil al-Dhiyabi in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia for al-Hayat newspaper on 8, March, 2006 with Dr. Musa b. Muhammed b. Yahya al-Qarni.

Interview

Al-Dhiyabi: Tell us how you travelled to Pakistan, then Afghanistan and worked alongside the Mujahideen in the 1980s.

Al-Qarni: An academic course was being held in Peshawar, Pakistan. I was a lecturer in those days and I asked the university president to allow me to join the group that was attending the course in Peshawar. I also informed him that if I went there, I would try to learn about the Mujahideen’s conditions. I attended the course but found time to visit the battlefronts to learn about the life of the Mujahideen. I made the acquaintance of Shaykh Abdallah Azzam and Shaykh Abdul Rasul Sayyaf. In those days Shaykh Sayyaf operated a university called the ‘University of Call and Jihad’ in an area close to Peshawar that had been named the Village of Migration. It had been specifically established to house refugees from Afghanistan but most of the Arabs who had come to Pakistan with their families also lived there.

Al-Qarni: An academic course was being held in Peshawar, Pakistan. I was a lecturer in those days and I asked the university president to allow me to join the group that was attending the course in Peshawar. I also informed him that if I went there, I would try to learn about the Mujahideen’s conditions. I attended the course but found time to visit the battlefronts to learn about the life of the Mujahideen. I made the acquaintance of Shaykh Abdallah Azzam and Shaykh Abdul Rasul Sayyaf. In those days Shaykh Sayyaf operated a university called the ‘University of Call and Jihad’ in an area close to Peshawar that had been named the Village of Migration. It had been specifically established to house refugees from Afghanistan but most of the Arabs who had come to Pakistan with their families also lived there.

At that time Shaykh Sayyaf had been elected as president of the so-called Ittihad-e Islami, the Islamic Union for the Liberation of Afghanistan. This group was formed after Muslim ulema and preachers made efforts to unite various Mujahideen factions in one body, so they formed Ittihad-e Islami and elected Sayyaf as leader because he had studied at Al-Azhar and spoke Arabic well.

This encouraged the Arabs to go and settle there. Their destination was where Sayyaf resided because first of all he was the president of Ittihad-e Islami and this gave him legitimacy in their eyes and he was also proficient in Arabic. For this reason he had a guest house in the village. Indeed I was a guest there for a long time. This was the beginning.

Afterwards I wanted to stay with the Mujahideen longer. Consultations were held on how I could spend a long time with the Mujahideen. Since Shaykh Sayyaf had a university for call and jihad, he told me: I will petition to let you become a lecturer at my university.

He made an application to the state to allow him to invite lecturers to teach at the university. The application was referred to Medina’s Islamic University, which responded by dispatching to him five instructors to teach at the University of Call and Jihad, and I was one of them. This went on for two years. Actually I played a role that was different from the four other lecturers whose tasks were confined to teaching.

Al-Dhiyabi: Who were your colleagues at the University of Call and Jihad?

Al-Qarni: They were Dr Hamdan Rajih al-Sharif, who is a retired professor now; Dr Ibrahim al-Murshid, who now teaches in Al-Qasim; Shaykh Rashid al-Ruhayli, a retired Islamic University professor who is over 80 now; and Professor Dakhilallah al-Ruhayli who continues to teach at the Islamic University. I was the fifth. As I said before, their role was confined to teaching at the university but my role, by virtue of my acquaintance with Shaykh Sayyaf and the Mujahideen, combined teaching at the university with visits to the front to advocate the faith and give lessons in religion and Islamic shari’ah to the young Mujahideen and also to take part in some operations.

Al-Dhiyabi: What form did the advocacy of the faith take in those days?

Al-Qarni: Many Arab young men who had joined the jihad lacked a proper Islamic education. Indeed a large percentage of them had lived a dissolute life before. Some did not become upstanding human beings until they decided to join the jihad. They became honest persons and immediately left to join the jihad. I know some young Mujahideen who were later killed in the fighting – I wish God may count them as martyrs – who had led dishonest lives before and indeed some had been really dissolute. But they were attracted to jihad.

This fact actually helped me in my work as advocate of the faith because I realised that many of those dissolute young men had something good inside them but never found the proper environment that would nurture them so they fell into an immoral mode of living. When they first came to us, some of them did not even know the rules of prayer or ritual cleansing prior to performing prayers. They had only come to fight.

My field of expertise was shari’ah-related and I taught the rules of physical purity before performing prayers and the rules of worship. I instructed them in the rules governing jihad, invasion, war spoils and combat and when they should fight and when they should refrain from fighting. So they attended courses in these matters. At the same time they attended military courses and received instructions from military experts.

Al-Dhiyabi: Did you yourself attend military courses? What did these courses focus on?

Al-Qarni: They focused primarily on developing the quality of endurance. As you know, Afghanistan has a mountainous terrain that has no paved roads for vehicles. So the trainees had to learn to tolerate hardship, to climb mountains and walk for 10-12 hours a day while carrying their personal effects, weapons and food for the trip. It was important to develop their power of endurance.

Secondly they were trained in the use of personal firearms. They were in a war. They had to carry their personal weapon, a Kalashnikov rifle, and know how to use it and how to use a pistol as well. Of course military training differed from one fighter to another according to personal aptitude and the role each was expected to play. Some confined themselves to learning how to use a Kalashnikov. Some trainees wanted to learn personal combat but others wanted to learn how to use antiaircraft guns and anti-tank guns. Others wanted to learn how to use mines, how to manufacture them and how to dismantle them, etc. The military courses differed in these details according to the type of trainee. Most combatants received training only in the use of personal firearms, Kalashnikovs and pistols.

Al-Dhiyabi: Did anyone receive training in suicide operations?

Al-Qarni: No, there were no suicide operations at the time. The young men used to attack tanks and fighter aircraft with their personal weapons. The battle was open. The Russian bases with their tanks and planes were there. You had your weapons and you could go and fight them face to face.

Al-Dhiyabi: Is it true that the university where you and your four colleagues worked turned into a station for the relay of intelligence data? Was the Village of Migration also a channel for intelligence operations?

Al-Qarni: It is necessary to have intelligence work. This is a normal state of affairs. It was not possible for the combatants taking part in the jihad in Afghanistan not to be backed by an intelligence apparatus. It is simply impossible to operate without intelligence in any country, including Pakistan and the United States. Even the enemies, the Russians, had an intelligence apparatus and sometimes they had moles in the ranks of the Afghan Mujahideen. It is normal. However, we never saw any of the intelligence work. The intelligence personnel did not interact directly with the Mujahideen. They worked directly with the politicians.

Al-Dhiyabi: The Mujahideen killed a group of people who used to work with them, I mean they executed them saying that they discovered that they had been providing information to other parties.

Al-Qarni: This took place in the later stages. In the early stages, the jihad was out in the open. Public operations do not provide an opportunity for concealment. I will give you an example. Sometimes certain countries would send intelligence operatives and indeed some of them might have been sympathetic to the communists. Indeed we know that some Arab countries were sympathetic to Russia. These countries used to send intelligence personnel. What happened to those people? At first they were received as guests and then invited to join the Mujahideen in combat. What would such a person do? He would be forced to become a combatant or if he was an intelligence agent, he would remain in the rear among the migrants and civilians. He could not go to the front because he would either be killed in combat or have his cover blown. These people did not want to die especially when faced with the enemy. When you confront the enemy, you must be prepared to die.

Al-Dhiyabi: How many stages did the Afghan jihad go through in the 1980s?

Al-Qarni: I would say the first stage lasted from the beginning of jihad until the collapse of Kabul’s communist regime and the Mujahideen’s capture of the city. The second stage was the stage of internal conflict among the Mujahideen factions, the infighting. During this period, we isolated ourselves from them. After the Mujahideen entered Kabul, I returned to Saudi Arabia and refused to participate in any actions after that.

Al-Dhiyabi: When exactly did you return?

Al-Qarni: The problem is that I do not remember dates well.

Al-Dhiyabi: In the early 1990s?

Al-Qarni: Approximately.

Al-Dhiyabi: Prior to the Taliban era?

Al-Qarni: Yes, before the Taliban. When Ahmad Shah Massoud entered Kabul and Najibullah’s regime fell, I left. I believe this happened in the 1990s. I and many other brothers who had gone to the jihad in Afghanistan returned home.

Al-Dhiyabi: Did Osama Bin Laden return with you?

Al-Qarni: He returned to the country, but went back to Afghanistan later.

Al-Dhiyabi: Do you remember the date?

Al-Qarni: Frankly, I cannot remember dates at all.

Al-Dhiyabi: I have heard that the Mujahideen used to refuse to memorise Western calendar dates.

Al-Qarni: No, I am not like that. First of all most of those who joined the Afghan jihad were not known by their real names but used aliases such as Abu-this and Abu-that. I used my real name everywhere I moved in Pakistan.

Al-Dhiyabi: Was Bin Laden’s moniker Abu Abdallah then, the same as today?

Al-Qarni: Yes, Bin Laden was always called Abu Abdallah from the time he went there until today. He is well known. Everyone knows Bin Laden.

Al-Dhiyabi: Sulayman Abu Ghayth was with you in those days. Do you know him personally?

Al-Qarni: I do not know him.

Al-Dhiyabi: Did you know Abu-Sulayman al-Makki, that is Khalid al-Harbi?

Al-Qarni: Yes, we were acquainted with him at that time. He was one of the first Mujahideen. He later went to Chechnya.

Al-Dhiyabi: Let us talk more about your stay there.

Al-Qarni: I stayed there for the first two years. Then the two years of my appointment as lecturer on loan ended. I had earned a sabbatical year by that time from my original university. I took that year because I wanted to return to Pakistan on another appointment on loan. Our original university decided that two years were enough and terminated the loan programme. However, I spent my sabbatical there. This means that I spent three years in Pakistan and Afghanistan. Later on I returned to Afghanistan for another two years, which means I spent a total of five years there.

Al-Dhiyabi: Who took care of your family during those years?

Al-Qarni: I still had my salary from the university and my wife’s brothers lived close to her. Every six months I would go back and spend two weeks with my family. This happened during the school year. During the summer vacation I would take my family to stay with me there. I had a house in the Village of Migration. I built a house there. I stayed there for three consecutive years but I continued to visit that university in later years during the summer vacations.

Al-Dhiyabi: Is that university still operating?

Al-Qarni: No, it is closed now.

Al-Dhiyabi: Did you encourage extremism in those days?

Al-Qarni: It was not called an extremist attitude at that time. Fighting the communists was the prevailing idea. Today it is called extremism. In those days it was called jihad. A Saudi architect was the one who founded the college of architecture at that university. He was a well-known brother who played a significant role in supporting jihad. He was a professor at King Sa’ud University and had an architect’s office in Medina. His name was Dr Ahmad Farid Mustafa.

Al-Dhiyabi: How did the university operate?

Al-Qarni: Part of the curriculum of the Call and Jihad University was to instruct and train students in jihad. They were sent into Afghanistan. It was a two-hour walk between the Village of Migration and the Afghan border from the direction of Jalalabad. During the Thursday-Friday weekend groups of university students would go to the front and help the Mujahideen.

Al-Dhiyabi: Who used to train them, intelligence personnel?

Al-Qarni: No, they had instructors. The Arab camps had Arab instructors, some of whom were retired military officers with good experience. The Afghans had their own instructors. The Pakistani army also provided material and moral support.

Al-Dhiyabi: At that stage Bin Laden operated under Abdallah Azzam’s command, right?

Al-Qarni: Yes.

Al-Dhiyabi: Did Bin Laden express his opinion on military matters?

Al-Qarni: He certainly did and his views were respected but he could not dictate his views. They had something that operated like a council and it was this body that debated the Mujahideen’s affairs.

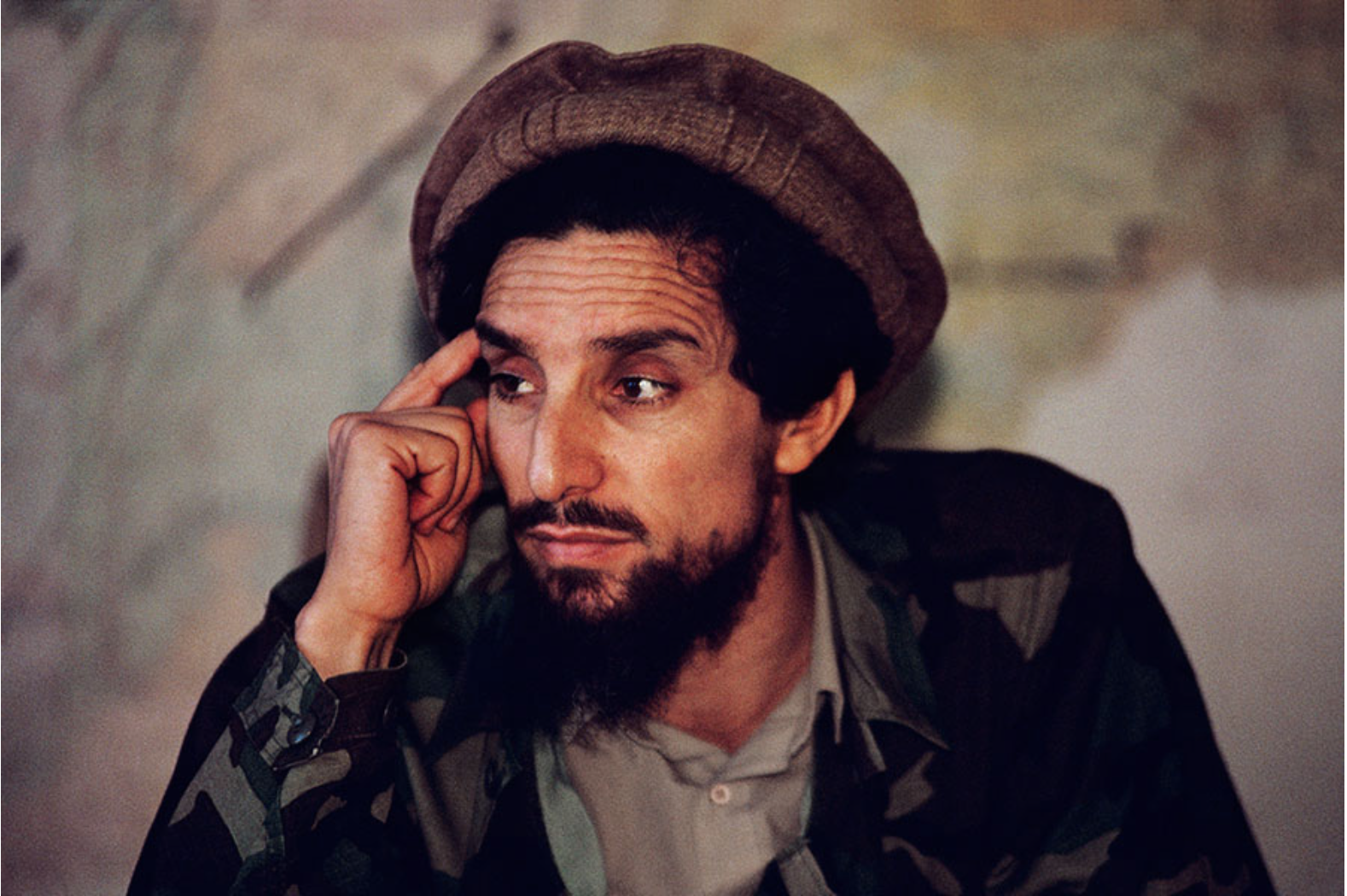

Al-Dhiyabi: Describe the relations between Ahmad Shah Massoud on the one hand and Abdallah Azzam and Bin Laden on the other.

Al-Qarni: Shaykh Abdallah Azzam believed that no-one among the Mujahideen had Massoud’s stature. He used to call him the hero of the north. I remember that I once asked him about his opinion of this man. Now the Arabs did not like Ahmad Shah Massoud – this is something that needs to become known. The Arabs hated him for several reasons. First of all most of them were influenced by Hekmatyar and lived as his guests in his camps. It was well known throughout the jihad years that Hekmatyar was Massoud’s greatest enemy. The Arabs were influenced by this enmity and became hostile to Massoud on these grounds. Indeed some Arabs hated Massoud more than Hekmatyar himself.

Al-Dhiyabi: Am I to understand that Hekmatyar welcomed the Arabs as his guests and incited them against Massoud?

Al-Qarni: Yes, this is a point that should become known. Massoud lived in northern Afghanistan, nearer to the Russian positions. He was not close to Pakistan. It took people 20 days to reach Massoud’s positions from the Pakistani border. As a result Massoud did not have an office in Peshawar, nor an information representative. He was stationed in the north directly on the combat lines with the Russians. In contrast, Hekmatyar and Sayyaf had camps and operated on fronts that were very close to Pakistan in the Pashtun region. Most of the Arabs who came to Pakistan and Afghanistan were on the side of Hekmatyar and Sayyaf. You could say that 95 per cent of the Arabs who joined the jihad divided themselves between Hekmatyar and Sayyaf. A small percentage joined Yunus Khalis and Jalaluddin Haqqani.

Very few Arabs joined Ahmad Shah Massoud. There few of them and we knew every one. This was the first factor that made the Arabs hate Massoud, namely, Hekmatyar’s enmity towards him.

The second reason why the Arabs hated Massoud, may he rest in peace, was that he was a methodical, strategic thinker. Combat is an organised affair, not a chaotic operation. The Arabs, many of them or actually most of them who came to carry out jihad, were not fond of military discipline. They were disorganised. Some came and stayed for one week only. They would join an operation, fire their weapons, storm a position and then return. Some stayed for a month or two and so on. For this reason the fronts on which Sayyaf and Hekmatyar operated were wide open places where people came and went.

Al-Dhiyabi: Are you telling me that Hekmatyar’s and Sayyaf’s guest houses were like open coffee shops?

Al-Qarni: I mean that they did not impose a strict regimen or force the Mujahideen who joined them to stay for a particular period. This is what I mean. Massoud was the opposite. He did not accept anyone who came unless he was prepared to stay on and operate under his command. He did not allow anyone to go and carry out operations except when he expressly ordered him to do so. The Arabs operating on the fronts of Hekmatyar and Sayyaf were independent. They could carry out their own operations. They did whatever they wanted without supervision. There was no-one to hold them accountable.

A group of Arabs joined Massoud in the early days of jihad. They went there with the same mindset with which they dealt with Sayyaf and Hekmatyar. After they joined Massoud, they planned and carried out an operation all by themselves without his knowledge. They attacked Muslim, not Russian, convoys. When Massoud learned of this, he put them in jail and they were only released after a lot of pleading and intercession by certain quarters. So those who were imprisoned by Massoud returned to Hekmatyar in Peshawar and they had developed an unbelievable level of hostility towards Massoud because he had jailed them and disapproved of their behaviour.

Shaykh Abdallah Azzam visited Massoud after a lot of negative talk was heard about him in Peshawar. Some accused Massoud of being an agent of the West. They said this because his father had been a general in the Afghan army and the children of generals were sent to Western schools. Because he had studied in such schools, they accused him of being an agent of the West. This was one thing. He was also accused of immoral actions. Some people actually levelled accusations of immorality against him. The Arabs spread a lot of negative propaganda about him in Peshawar. This reached the point where they were discussing whether it was proper or not from an Islamic viewpoint to support him with money.

Al-Dhiyabi: It has been said that Massoud is a Shi’a.

[NB.this was another accusation some of the Afghan Arabs who were Salafi in outlook made against Massoud. The former considered Shi’ites to be heretics at best and infidels at worst, and made this accusation against him. Ahmed Shah Massoud was Sunni of the Hanafi school of jurisprudence with an inclination towards Sufism, a mystical form of Islam. He had friends from the Shi’ite Hazara community who he considered to be part of Afghanistan’s future.]

Al-Qarni: No, he is Sunni. I remember that when there was too much talk about him in Peshawar, a session was held to try him in absentia. Two people acted as his defence and 21 acted as his accusers. The two who defended him were Algerian nationals: Abdallah Anas, who now lives in Britain and is Shaykh Abdallah Azzam’s son-in-law, and a man called Qari Abdelrahim. They had lived with Massoud and knew him well. On the other side 21 people including Algerians, Egyptians and Yemenis acted as accusers. There were no Saudis among them. They accused Massoud of offences amounting to apostasy. The trial was held and among those present were Abdallah Azzam, Shaykh Abd-al-Majid al-Zindani and Osama Bin Laden.

Al-Dhiyabi: How long did the trial last?

[The word ‘Trial’ here is not meant in the Western sense. Trial here resembles a traditional ‘majlis’ or ‘Jirga’ from traditional Muslim societies were a gathering would preside to resolve an issue. It was usually lead by Elders or Sheikhs versed in religious lore, some witnesses who would ensure that it remained impartial and fair. You would have defenders and accusers who would lay out their case, the Sheikhs/Elders would ensure that the matter comes to a negotiated settlement. The settlement was not always about the right and wrong but about equity.]

Al-Qarni: It lasted a whole week. Of course they asked me to give testimony but I refused to get involved. Nevertheless I followed what was happening. I received my information from Shaykh Abdallah Azzam, Shaykh Al-Zindani, Bin-Laden, Abdallah Anas and Qari Abdelrahim. A curious thing was that a brother of Qari Abdelrahim, who was called Qari Said, was one of Massoud’s bitterest enemies. I ask God to forgive Qari and have mercy on his soul. After he returned to Algeria from Afghanistan, he joined the armed groups there and was killed. The 21 accusers failed to prove Massoud’s guilt on any of the charges they levelled against him. When the presiding committee announced its verdict, its members declared that they would not say anything either in praise or vilification of Massoud.

Al-Dhiyabi: What do you think of this verdict?

Al-Qarni: I think it was unfair. You should either prove a person’s guilt or exonerate him but the committee ruled this way because Osama Bin Laden and Shaykh Abd-al-Majid al-Zindani were more inclined to support Hekmatyar than Massoud. Additionally they did not want to go against the wishes of the Arabs who were in Peshawar, saying to themselves: All the Arabs in the city are against Massoud, so how could we praise him?

The only exception was Shaykh Abdallah Azzam, may he rest in peace. He said: As for me, I will praise Massoud until I go to my Maker, God Almighty. He left that trial session and began implementing a plan to praise Massoud. He wrote a book about him called “The Titans of the North”. He could not get it printed, however, because almost all of Peshawar was semi-owned by Hekmatyar and Sayyaf. Massoud had no influence there. So the book was not printed.

I once asked Shaykh Abdallah Azzam, may he rest in peace: Shaykh Abdallah, do you still believe that Massoud is the hero of Afghanistan? Azzam replied: Indeed he is the hero of Islam. After this I told myself that I should pay a visit to Massoud and get to know him from up close. Brother Abdallah Anas used to talk to me about Massoud. I used to see his jihad as a different form of jihad. The Mujahideen in southern Afghanistan conducted a form of guerrilla warfare. This means you cannot destroy your enemy but you can continue fighting forever. It was a form of hit-and-run warfare without a clear strategy. This is why Sayyaf, Hekmatyar, Haqqani, Yunus Khalis and all the other factions in Peshawar could not capture any of the major cities. They lived in the mountains, valleys and small villages, conducting a hit-and-run form of combat. They would carry out an attack, seize war spoils, but then the communists would come and expel them from the positions they had occupied, and so on. Massoud, on the other hand, conducted a form of regular warfare. He had a regular army and a clear strategy.