Paradise Lost: The Rise and Fall of Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi

I entered Najiyeh, a small town of no consequence, without their permission. The town claimed to be an ISIS principality. The claim seemed ridiculous but as we drove in to the town it seemed less so. They had fixed the prices, the markets were bustling, even the gold shops were open. It was a stark contrast to what I had heard about their ‘state’. I understood why the people accepted their rule; order is key in conflict especially in one as brutal as this. Even non-ISIS people in the surrounding countryside told me good things about them. “You could bring your case to their courts”, they would say, “and it would be resolved with out fear or favour”. Their entry reminded me of the Taliban being welcomed with loud cheering and flowers in Kabul but they left with the inhabitants shaving off their beards and smoking cigarettes even if they had never touched one before.

A few months later I met Abu ‘Ali in Tarsus, Turkey. The young commander from Ansar al-Sham looked like a young St. Paul, dark black beard with long hair that was slightly thinning on top. He was recovering from a leg injury that if miracles weren’t real, should mean him being minus one leg. The wound was horror personified. Abu ‘Ali informed me that the people alongside the local battalions had kicked ISIS out of Najiyeh.

“Why?” I asked.

“They were harsh people” he replied, I noticed disappointment in his face, it was as if they had betrayed the Syrians. The Revolution, if you will, had made these insignificant men into Mujahideen, warriors of God. Some of these men had been eking out their existence as smugglers, farmers or hiding from the authorities. The Revolution had made them. Now the likes of Abu ‘Ali who had emerged from the mosques calling for the removal of Assad, facing live bullets after Friday prayers were lectured to by Abu so-and-so al-Britani who, only six months ago, was checking out some winding girl’s batty rider in some funked up club. Here came Abu so-and-so to the land of Muslim scholarship and lectured the people on the intricacies of kufr, taghut, tawheed and the incompatibility of Islamic theology with democracy. Syrians didn’t need lessons in creed. They wanted to stop the barrel bombs from killing their children.

A few years later in Saraqeb, whilst filming with Jund al-Aqsa, I was told that the local leader of Ahrar al-Sham had shot the local ISIS emir in the back. The ISIS emir, a native of the city, considered it sacrilege to turn his gun against his co-religionists. However, the leader of Ahrar had no compulsion in dispatching him to eternity. The people had liked the ISIS emir but these same people had also defaced the testimony of faith in the Islamic State’s court house. They wrote sarcastic comments over it. ISIS would no doubt consider it apostasy, still none of the locals had renounced Islam but they too, like the Kabulis had shaved off their beards, increased their smoking even though they readily admitted that smoking was ‘forbidden’ in Islam. More recently, incredulously, I heard an Iraqi man preferring the Iranian backed Shi’te militia, the Popular Mobilisation Group in Mosul instead of ISIS. Moslawis had few issues in raising the Iraqi flag and lowering the ISIS flag, even though everyone knew that the former banner was born in the gentlemen’s clubs in London and the latter in Abbasid Baghdad. And yet without any sense of irony, Moslawis had preferred the latter. Why when everyone professed to be Muslims, did the ISIS come to this? Why did al-Baghdadi’s nascent project fail?

Arguably, ISIS did not lose because of a determined opponent, for they are not short of courage and military experts attest to their mastery of asymmetric warfare. ISIS lost because the local populace stopped believing in them. So much so that the people reviled them more than they reviled Assad. People hate Assad because he killed their children but they hate ISIS for stabbing them in the back whilst they were trying to overthrow former. Assad never claimed to be ‘Islamic’ and in a way, nothing was expected from him. He could do what he wanted, he was after all from a long tradition of Middle Eastern tyrants who crushed uprisings whether they be Muslim Brotherhood, Iraqi marsh Arabs or Shi’ites. Brutal cruelty was expected. Even though the deaths inflicted by ISIS remain minuscule compared to the former, when ISIS claimed to be ‘Islamic’ and acted with such wanton cruelty, it provoked disgust and revulsion from even the most dissolute of Muslims. Even that hard drinking, stripper ogling Muslim who puts his head down on the carpet once a year if that, knows that the bar has been raised. He knows that it is unbefitting for a ‘holy warrior’ to behave thus.

Whatever Graeme Wood argues about ISIS and its level of ‘Islamicness’, what Ahmed on the street recognises instinctively is that al-Baghdadi and his group are far from ‘Islamic’; no Fatwa needed. Muslims are inculcated with a conception of what a Mujahid or ‘holy warrior’ is meant to be. The stories of the Companions of the Prophet, Hamza the lion of God or Omar Mokhtar the lion of the desert, both usually in the guise of Anthony Quinn are found in their mothers’ milk. Sons are named Mujahid, Ghazi, Faris and Shaheed in the hope that they epitomise that exceptional person who perfects his moral and martial virtues in a situation where bestial brutality is permissible and yet he manages to retain his humanity. The nobility of man is truly tested in war.

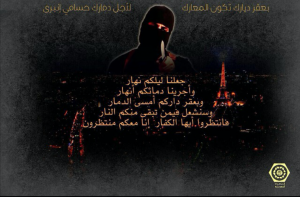

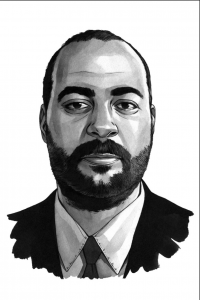

It is here that al-Baghdadi and his men have failed so miserably. His heroes who populate the telegram channels make Muslims recoil. Abu Muhammad al-Adnani, his deputy, is certainly eloquent and no doubt courageous but ordinary in his brutality and harshness, no matter how many texts his eulogist claims he has studied. Jihadi John too is ordinary in his inhumanity. Go to the local halal butcher on Harrow Road, London and he will tell you that Islamic rites dictate that an animal should be given its final sip of water and slaughtered away from the gaze of another animal to lessen its distress and that of the other animals. Yet, here stands Jihadi John slaughtering innocent men in front of the whole world so brazenly. There is no sense of shame, even Cain felt ashamed after he killed Abel.

There seems to be something thoroughly modern about Jihadi John’s actions as he points that knife at you. Arguably, Jihadi John’s actions have roots in the London of the Nineties, when Jihadi snuff tapes were sold openly outside mosques. These videos showed in graphic detail the exploits of the Chechen mujahideen against Russian aggression in Chechnya. One of the Imam’s who used to teach in Lisson Green youth club, where Mohammed Emwazi used to attend, recalls that soon those tapes:

“…became dark there was a Russian beheaded by some Chechens, and whenever I saw the brothers, some of them would creep up from behind and greet you by cutting you in the neck.”

Perhaps the mood music for Mohammed Emwazi’s deeds had been set up then. The Imam continues:

“I remember, even at the time that this is not how you greet each other, and I always reminded the brothers that the point of Jihad is not to be blood thirsty and I used to quote the hadith of the Prophet: “Don’t look forward to meeting your enemy, but if you meet him remain steadfast.”

Jihadi John is unrecognisable as a mujahid by your average Muslim, but take Jihadi John to the cold harsh streets of West London and any road man who listens to Stormzy recognises his deed to be pure gangsta.

The mujahid of now is very different from the mujahid of then. Let us demonstrate this with a tangible example, let us use a paragon of a holy warrior of the 19th century, Abdel Kader al-Jaza’iri. He was also known as the Commander of the Faithful although, admittedly, under the suzerainty of the Sultan of Morocco. Abdel Kader, like al-Baghdadi, tried to build a state by uniting the various tribes in Algeria and was harsh to those who collaborated with the French. Like al-Baghdadi, he was a scholar, a jurist and descended from prophetic lineage. He fought the French invaders and was described by his foes and friends alike as a fearless military genius and as illusive as al-Baghdadi. William Thackeray wrote of him:

Nor less quick to slay in battle than in peace to spare and save,

Of brave men wisest councillor, of wise councillors most brave;

How the eye that flashed destruction could beam gentleness and love,

How lion in thee mated lamb, how eagle mated dove!

And yet the gulf between al-Jaza’iri and al-Baghdadi, as Thackeray’s poem shows is vast. Whilst war is harsh and brutal, the former was known for his chivalry and treated his prisoners humanely; so much so that these prisoners of war petitioned France to release him when he found himself in the same predicament. Some even offered to be his guard of honour on account of the kindness he had shown them. Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi showed no quarter. He burns and drowns his prisoners alive. Abdel Kader condemned his brother in law for massacring prisoners, the latter revels in it and encourages it. The sadism is so creative that one wonders whether there is a whole unit in Raqqah whose sole job is to come up with creative and cruel ways to execute people. Al-Baghdadi, this product of the Iraq war, has embraced terror wholeheartedly.

Abdel Kader is careful not to harm civilians. When sectarian riots broke out in the Christian quarter of Damascus he saves countless number of Christians. Al-Baghdadi sends a suicide bomber on Palm Sunday to a Coptic church in Tanta and murders countless. The former honoured men of religion; priests were allowed to minister to the French POWs and act as go-betweens. The latter kidnaps the Jesuit priest Father Paolo Dall’Oglio. The fate of the man committed to building bridges between faiths, remains unknown. Abdel Kader stops the practice of beheading prisoners, the latter puts their heads on social media. The former releases those who renounce their faith to escape, al-Baghdadi doesn’t care if they have converted or not. If they do not accept the Caliphate he’ll send one of his soldiers to ram an explosive laden car into a busy market or get one of his soldiers to line up in rows and offer the evening prayer and then detonate his explosives belt.

As one former ISIS fighter told me, “Dawla [Islamic State] isn’t all that it’s made out to be you know.”

You think? One can’t help but ask how many lives he had to take to come to that conclusion?

“Don’t worry” he reassures me, “they were apostates anyway.”

Fantastic. Lessons have been learnt then, no nightmares when he goes to sleep.

On a final note, Abdel Kader realised that noble ends have noble means. He surrendered because he realised that his battle with the French would be too hard on the surrounding tribes and submitted to Providence. For as the old Islamic adage goes, victory lay in His hands. And yet History wrote this loser to become the victor. Abdel Kader gained universal admiration. His enemies who once reviled him honoured him. The ultimate proof of his moral character comes from the people of Bordeaux who voted to get his name on to the ballot paper for the French presidential elections. As the Progres d’Indre et Loire notes:

“We have learned that certain voters of Bordeaux were so impressed by the manners, the character and royal air of Abd el-Kader, they put his name on the ballot for president of the Republic. If this idea spreads it will hurt Louis-Napoleon. To be a good president one must have a reputation of courage, wisdom and talent. Of the two, would not Abd el-Kader better meet those conditions?”

ISIS and The Challenge of Modernity

In Reims, the nameless flowerless grave of Saïd Kouachi, the Charlie Hebdo attacker, is slightly apart from the other dead souls. It is as if he would offend the repose of the interred Muslim souls. In this solitary place one of the sons of the dead asked me what I was doing taking photographs of this newly dug grave. I couldn’t deceive the man and told him whose grave it was. The Franco-Algerian spat on Kouachi’s grave and cursed him. The man, no doubt loved the Prophet just as much as Saïd Kouachi did and yet he shouted: “How is my father going to have peace next to this dog!”

Kouachi didn’t belong to ISIS, but Kouachi and indeed Ahmed Coulibaly one of his companions had the same father. I pitied Saïd Kouachi, few Muslims will ever raise their hands in prayers for this man’s soul. His children would be ashamed to acknowledge him and they will feel strongly the shame of Oedipus Rex himself. I would wager that if I had asked that French Algerian visitor to his father’s grave whether Kouachi was a Mujahid, I would know what that reply would be. He may have understood Kouachi’s anger, he may have experienced the deep racism of French society towards its Muslim population, but I know what his reply would be. I have asked similar questions in all the major terror attacks in the European mainland, Paris, Brussels, London, Stockholm and the average Muslim knows that these men are far from Abdel Kader or Hadji Murat. Kouachi lies in a nameless grave remembered by none. Abdel Kader has a city named Elkader no less than in Iowa and Hadji Murat has a novella written in his honour by an old foe of his, Leo Tolstoy. Both Abdel Kader and Murat lost, and yet Providence in spite of the victor writing history, has preserved their names. They inspire universal admiration. They were ‘holy warriors’ if you will, where as Saïd Kouachi at best was just a ‘warrior’ and at worst a butcher- and a very modern butcher at that.

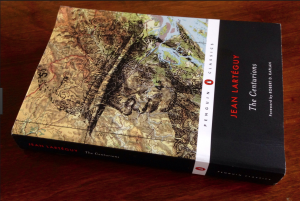

Let us use General Petraeus’ playbook, Jean Lartéguy’s, The Centurions, to demonstrate the last assertion. Ostensibly, The Centurions follows the journey of several French paratroop officers from defeat at the hands of the Communists in Indo-China to a victory of sorts in Algiers. But in the process of defeating the F.L.N in Algiers they lose something of themselves. Whilst the novel is blind to the century of oppression that Algerians tasted, it is nevertheless a deep rumination on modern warfare and based on Lartéguy’s own experiences as a paratrooper and war correspondent. Lartéguy realises very quickly that the F.L.N used Jihad as a rallying cry for independence, but what it produced was something thoroughly different: it created an Ersatz France. This is why the novel is useful for this essay. Arguably, ISIS too has done the same and produced something that appears to be a bastardised version of what a caliphate is ‘meant’ to look like in their very modern mindsets.

In some ways what Abbas and Mohammed expected of these very ordinary fighters who called themselves mujahideen were exceptional standards in virtue. What they got instead were merely the usual fare. They were like everyone else, they looted, they robbed, they killed and behaved just like every other militia in the world. There was a banality in them and an absence of holiness. Al-Baghdadi was just like Saddam Hussein, ordinary. He was part of the fabric of rulers and tyrants in the region’s bloody history from Saffah to Sisi who massacred men for worldly authority. There was very little difference between a mujahid, a warrior and a terrorist. It is as an F.L.N leader opines in The Centurions:

“what difference do you see in the pilot who drops cans of napalm on a Mechta from the safety of his aircraft and a terrorist who places a bomb in the Souq- the terrorist requires far more courage.”

But the F.L.N leader forgets that what was expected from the Mujahid was not just the courage to step into a truck laden with explosives. The modern mujahid might be a master of asymmetric warfare but he was not meant to be stuffing explosive booby traps into dolls and toys such as those found in Mosul. For whilst the Prophet has said “war is trickery” would he sanction such an act? Does the Muslim martial tradition not abhor such things? Otherwise surely the ‘holiness’ of the warrior has been lost to the banal ordinariness of all warriors. Is he merely an ‘atheist’ mujahid like Mahmoudi in The Centurions, who prays but does not believe in God? Is he then the sort of Mujahid who has to suppress his moral conscience for the sake of victory? The modern Jihadi seems to have sent paradise to hell, and is simply not too bothered if children, the elderly, women, monks, fruit trees or the enemy’s flock are destroyed, even if his religious tradition forbids him from touching them. This Jihadi seems to revel in it. Mohammed Rezgui, for instance, filmed himself elated before gunning down innocent British tourists in Sousse, Tunisia. But the post mortem autopsy seems to suggest that the drugs found in Rezgui’s body created:

“The feeling of exhaustion, aggression and extreme anger that leads to murders being committed. Another effect of these drugs is that they enhance physical and mental performance.”

Why would a holy warrior need to take an amphetamine type drug in order to commit a ‘virtuous’ act? What exactly was he suppressing? Was he like those French paratroopers who were suppressing that feeling of guilt that the intangible soul within knows is committing something morally reprehensible?

In some ways then, the Jihadi is so thoroughly modern that the average Muslim on the streets turns around and says: hang on, this isn’t what we were told by our mothers and fathers. We weren’t reared on Osama bin Laden or Zawahiri but on Hamza, the Lion of God. Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi had become just like the French Paratroopers and F.L.N leaders in The Centurions: in order to win they had to loose their souls.

Come, let us be generous, and afford al-Baghdadi some empathy as we do with the protagonists in The Centurions. We are generous towards Esclavier even as he slits the throats of all the men in an Algerian village. Perhaps the reason why al-Baghdadi joined Abu Mus’ab al-Zarqawi’s al-Qaeda franchise was for similar reasons outlined by the head of French intelligence in Algeria, Jean Vajour who noted the heavy handed tactics of the French:

“To send in tank units, to destroy villages, to bombard certain zones, this is no longer a fine comb, it is using a sledgehammer to kill fleas. And what is much more serious, it is to encourage the young- and sometimes the less young to go into the Maquis [rural guerrilla fighters]”

Perhaps the heavy handed tactics used by US army in Fallujah led the not so young al-Baghdadi, to join the insurgents. Maybe at one point this Abu Bakr was just an ordinary man, a devout man who to all accounts lead prayers at his mosque, played around with the kids, listened quietly to the complaints of the locals and advised them on Islamic law since he possessed a doctorate. On Fridays he played football on the dusty streets of North Samarra, a suburb of Baghdad. Maybe this is how his life would have continued till the end of his days. But war has a way of twisting men’s souls, and just like the French paratroopers in The Centurions who spent several years in the camps of the Communists, Abu Bakr too ended up in Camp Bucca. His captors taught this Dr. Ibrahim Awad or Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi a thing or to. Like officer Mirendelle in The Centurions, he too learnt how to mediate, how to win alliances and how the Americans behaved. Perhaps just like the French Paratroopers who learnt much from the Communists and applied the lessons with deadly effect in Algeria, Abu Bakr too learnt things in Camp Bucca and applied it to deadly affect. He certainly learnt how to put people in orange jump suits. When he emerged, he experienced the intensity of asymmetric warfare, he learnt that stuffing bombs inside corpses and dogs were effective, how to create grey zones by dividing Sunnis from Shi’ites, how to sit completely still when a drone flew ahead and the art of illusiveness. He learnt all such things over the years without rest or respite- constantly hunted with a price on his head. Perhaps, by the time the Syrian uprising began, he became that amoral man in The Centurions, Captain Julien Boisfeuras, an expert in unconventional and political warfare, who like the real life monster captain Paul Aussaresses tortured, waterboarded, raped, electrocuted a man in the balls, if only to achieve victory. Abu Bakr al-Baghadi, in the light of modern warfare, fitted in with that landscape. In fact perhaps, all of us given the circumstances, could become just like him. Consider Youssef Ben Khedda, a pharmacist, whose hands according to Alistair Horne’s masterful A Savage War of Peace, were clean. Horne writes:

“He wrote a joint letter to Alger Républicain complaining about the blind arrests. Two days later he too was in prison, followed shortly by his fellow signatories; immediately he was released, five months later, he joined the F.L.N”

Could this story of ‘radicalisation’ not apply to al-Baghdadi or even us? Isn’t that human nature? When the Nazis invaded France what tactics did the Free French use against them? Billion dollar armies can afford to have rules, resistance movements have to make conscious choices to have them or not. It even begs the question whether the likes of Abdel Kader could even be allowed to flourish in the murky ethical terrain of modern warfare.

And yet it is perhaps what Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi had become that the Muslim guy and gal on the street recoils at. “That’s precisely it” says one worshipper in Norbury mosque, “we can all be like him but that’s not what a mujahid is meant to be! He’s meant to be like Imam Ali when the Arab spits at him as he is about to kill him, he leaves him”. The anger is visible in his face, Abu Bakr doesn’t deserve the title of mujahid. Perhaps the political philosopher John Gray is spot on when he says that Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi’s Islamic State:

“…shares more with the modern revolutionary tradition than any ancient form of Islamic rule. Though they’d hate to hear it, these violent jihadists owe the way they organise themselves and their utopian goals to the modern West”

And everything he does seem to support Gray’s view. Al-Baghdadi, calling on terror attacks on the West, is following Abu Bakr Naji’s tactics outlined in his tract, The Management of Savagery. The intention is to create grey zones that divide the population into an ‘Us’ and ‘Them’ scenario. These tactics, these very modern tactics were advocated by the Brazilian guerrilla leader Carlos Marighela, and also used by the F.L.N as one of Lartéguy’s protagonists observes:

“…a bomb exploded….at the cafeteria some medical orderlies laid a child screaming with pain, on a stretcher- another bomb exploded in 5 October in Algiers killing nine Moslem passengers. Horror reigned in Algiers- horror was succeeded by fear and hatred- Moslems began to be beaten up without rhyme or reason. Europeans got rid of their old Arab servants and Fatmahs who had been part of the family for twenty years. Within a few days Bab al-Oued witnessed a distinct rift between the Moslems on one hand and the Jews and Europeans on the other. This was exactly what the F.L.N wanted to divide that ill-defined zone and split up its inhabitants who tended to resemble one another more and more. For they had so many things in common, certain nonchalance, love of gossip, contempt for women, jealousy, irresponsibility and inclination to day dream.” [pp.452-453]

ISIS realised what the French paratroop officers understood in fighting the F.L.N; in order to win they had to get on an equal footing with the native population. They had to get “as covered with mud and blood as they are. Then one shall be able to fight them, and in the process we’ll lose our souls, if we really have souls.” And so the paratroopers extended the ill treatment of native Algerians and did things irrespective of legality; they massacred, tortured and raped. They took the local women away, treated them like queens as they ironed and washed for them and then returned them to their men. The French thought they were freeing the Algerian woman from Arab patriarchy and emasculating them by showing how little control they had over them. But when they met a troublesome one, they simply raped her. As one of the Paratroop officers recognised:

“…the ghastly law of the new type of war. But he had to get accustomed to it, to harden himself and shed all those deeply in-grained, out-of-date notions which make for the greatness of Western man but at the same time prevent himself from protecting himself”- [p490]

And the truth was these French paratroopers as Lartéguy says, fought an enemy very much like themselves. Some of the F.L.N leaders were former officers, some were university educated metropolitans treated with disdain in Paris cafes like many French of North African descent are treated to this day. They were thoroughly modern creatures and so employed the same tactics as the paratroopers. They massacred Pieds Noirs civilians in Philippeville, they liquidated their own members, gouged out the eyes of collaborators and believed that the end justified the means. Arguably, ISIS mirrors what the F.L.N did in Lartéguy’s novel. But where as the F.L.N in Lartéguy’s model understood that they were moderns somewhere along the line, Abu Bakr and friends did not understand the fact that they were too.

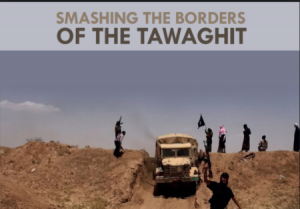

For al-Baghdadi is in a sort of denial. He has failed to deal with modernity itself and in it lie the seeds of his defeat. It is this reason that made the people of Najiyeh boot ISIS out, the commander of Ahrar shoot the ISIS emir and the locals scrawl sarcastic comments on their Shariah court. This inability to grasp modernity, to understand that a process has occurred between their ‘Islamic State’ and the past. The Muslim world has experienced a traumatic rupture, not just defeat, humiliation and loss but colonisation, industrialisation and societal changes which have fundamentally altered the times we live in. In the past, life was organised and configured differently, the same rules which applied to the pre-modern world cannot be applied anymore. The Islamic State is like a car crash victim who, after recovering, thinks he can just go back to living the same way when in reality his limbs do not function in the same way. He can’t come to terms with his accident and so disasters ensue. Since he can not remember what the past looks like before the crash, he conjures it up just like the F.L.N leader does in The Centurions:

“There’s only one word for me Istiqlal, independence. Its a deep fine-sounding word and rings in the ears of the poor fellahin [farmers] more loudly than poverty, social security or free medical assistance. We Algerians steeped as we are in Islam are in greater need of dreams and dignity than practical care. And you? What word have you got to offer? If its better than mine you’ve won.”

Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi came up with ‘Khilafa ‘ala minhaj an-Nubuwwa’-‘the Caliphate on the Prophetic Methodology’, and the Muslim world looked up for a second, with a sense of hope and nostalgia; for this was their historical past, just as the British looks to their Empire, their Raj and the Battle of Britain nostalgically, not quite coming to terms with the fact that they are no longer a great power. Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi tried to realise the word ‘Khilafa’. But what did the word ‘Khilafa’ mean in the context of modernity and the post-colonial world? In the Pre-Modern Islamicate, people were divided into millets or religious communities because that was the reality on the ground. Now we had the concept of citizenship, this is the new reality. ISIS denied this new reality and sought to extract the Jizyah, the poll tax from Syrian Christians thinking that it was more merciful on them than paying higher taxes. These Christians who had lived on that land for millennia would be paying this Jizyah to Abu Marwan or Luqman from Ghafsa, Tunisia. ISIS failed to comprehend that even if the Jizyah was lower, and the Christian is protected by the Muslim armies, in the modern context it is simply put, humiliation. We are all sons of egalité now, whether we like it or not. The Syrian Christian has for generations grown up with the concept of equality. In fact, he may be like the ancient Northern Syrian tribe of Ghassasina who preferred to pay a higher tax rate to the second Caliph, Umar, than accept the status of second class and pay the Jizyah. In the past, the French made Arabs in Algiers wear the necklace akin to the Star of David to signify that they had ‘submitted’ to French laws. Arabs accepted it in the 19th century. Jews wore different colours in the Middle East during the Medieval period. Modern man cannot accept any of these things, even if it is deemed for their own ‘good’. ISIS couldn’t come to terms with this.

In fact, al-Baghdadi creates what Benedict Anderson calls “an imagined community” through the use of powerful propaganda, tapping into the emotions of many Muslims. This isn’t just a cynical attempt, Graeme Wood is right here, ISIS are True Believers-zealots. They may have been former secular officers who were thrown into Abu Ghraib but, just like the F.L.N commander in The Centurions, they had rediscovered their religion, their reality had been shaken with the fall of the modern Iraqi state. These highly trained officers couldn’t just return to the coffee shops to smoke a fat Zaghloul and drink bitter coffee, lamenting the presence of US marines on their streets. That jarred with their sense of honour, no, they would return to Fallujah and Mosul where their families were and fight. These officers did what an Algerian officer in The Centurion did, they gave their failed country “a history and a personality.” They grabbed the black ‘Abbasid’ flag and made it synonymous with Islamicate. Heavily reliant on ‘salvation history’, they created a vision that the banner of Islam spread from East to West. They ignored historical reality where at one point there were three caliphates that vied for power with each other, and that even after the fall of the Abbasid caliphate in Baghdad, no caliph existed at all for several years. ISIS did what Lartéguy says happened in Algeria, they created a history based on the cemeteries of the dead not based on historical reality. It was Fake News caliphated. As one F.L.N leader says, congratulating a French paratroop officer on his country’s contribution to the creation of modern Algeria:

“The Algerian people have been scarred by war, their existence has been too disturbed to turn the clock back at this stage. You yourselves are creating Algeria through this war, by uniting all the races, Berbers, Arabs, Kabyles and Chaouias. The rebels should be almost grateful to you for the violent measures of repression you have taken.” [p473]

And so the invasion and the sectarianism within Iraq and lately Syria helped to create this ‘nation’ if you will. When ISIS broke through the Sykes-Picot border, it was seen as restoring parity between the oppressed and the oppressor. It was like Horne says of France’s defeat at Dien Bien Phu by the Viet Minh in 1954:

“Suddenly this unbelievable defeat deprived the French army of its baraka, [blessing] making it look curiously mortal for the first time.”

The breaching of the Sykes-Picot line was the biggest paradigm shift since Ben Ali fell in the Middle East. It showed the world and indeed Muslims that the status quo can be changed, that the West’s grip on the Muslim world was not supreme. This was Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi’s ‘Yes we can’ moment and perhaps his legacy even as we begin to write his obituary. In post-colonial theory at least, he had done what Franz Fanon believed was essential between coloniser and colonised. He had restored parity, not through the coloniser granting him his freedom which instilled an inferiority complex in the manumitted. Rather, he took it by giving the coloniser a bloody nose. When ISIS broke through Sykes-Picot, they had restored a sense of honour for many in the Middle East. Similarly, when the Islamic State reintroduced concubinage and traditional female roles, they reasserted this injured manhood. And yet at the same time, they displayed their inability to accept that modernity had changed us so fundamentally that Jefferson could own slaves and still be considered a ‘good’ and ‘virtuous’ man then. But today, should he practise the same thing, he’d be considered a monster.

ISIS may have signalled its independence by purporting to ‘mint’ gold coins and arbitrarily declaring ‘provinces’ all over the Muslim world and yet, just like the Algerian officer Mahmoudi in The Centurions, who knew that Algeria could not exist without France, the Islamic State also demonstrated that it could not exist outside of the modern world. The creation of uniform ISIS courts were in reality the importing of Western law courts, which made the Rule of Law the basis of the state. Partly, ISIS knew that it had to compete with that model and partly because it didn’t know anything else. On one hand, it was proof of their ingenuity at state building, but also an admission that the paradigm to beat was still the Western model. According to Wael Hallaq’s Impossible State, Islamic history didn’t have uniform law courts as we see them in modern nation states. Far from it, they were extremely organic and functional affairs tailored to the needs of the local community. The historical Islamicate had never made the Rule of Law, king. Now it did. Similarly, when ISIS introduced ISHS, Islamic State Health Services, it based itself on the British National Health Services, NHS, rather than the hospitals of Medieval Andalusia. ISIS then, could not exist outside of time, theirs was a modern project however much it tried to deny it. ISIS’ predicament was like that of the Jihadist who blew up the ancient Buddha statues or the temples in Palmyra for being an expression of infidelity and irreligion but did not realise that his Nike trainers were paying homage to a Greek deity.

In al-Baghdadi’s denial of modernity therein lies his demise. His group failed because the Mohammed and Ayesha in Raqqah and Mosul instinctively realised that they were un-Islamic in spite of the long beard, ankle swingers and tooth stick. It is likely that there will be other groups who will want to emulate ISIS, but for them to be successful they will have to come to terms with modernity. One suspects that they too will fail. Sometimes an old timer can grasp the un-tangible better than many learned men. These ancient looking men don’t know many religious texts but have an earthy piety and remain a reliquary of wisdom that sees things plainly.

“Now these youngsters,” says wispy bearded uncle Forid sitting in Brick Lane mosque waiting to meet his Maker, “are running around killing this and committing God knows what sin thinking that they are doing the Prophet’s work! Idiots! They are so far from him! When the Mehdi comes everything going to be fine.” Uncle Forid is resigned to the arrival of the Mehdi, the messianic saviour who will come at the end of time in Muslim apocalyptic narratives. Uncle Forid knows that the youth are too impatient, they want paradise now. They don’t want to lose. The youth forget that what goes on in the world is often a reflection of a sick heart. They forget that the Muslim pantheon contains plenty of winners but also plenty of losers; Abdel Kader, Hadji Murat, Imam Shamil, Omar Mokhtar but history honoured them because they remained true to their martial tradition and moral code. To eternity, it seems, winning isn’t everything. An anecdote of Omar Mokhtar told to me by a Tunisian activist is pertinent here: one of Omar Mokhtar’s Mujahideen demanded that two Italian POWs be given no quarter just like the Italians did to them. Omar Mokhtar replied: ‘They are not our teachers’. Whoever comes after the fall of Mosul will need to convince a sceptical Muslim population, tired of the killing and the blood, that they match up to mujahids like Omar Mokhtar.

This post was first published in Syria Comment additionally I add an embed version of Gillo Pontecorvo’s classic Battle of Algiers below based on the account of one of F.L.N leader’s memoirs who is also acting in the film.