From Afghanistan to Abaaoud

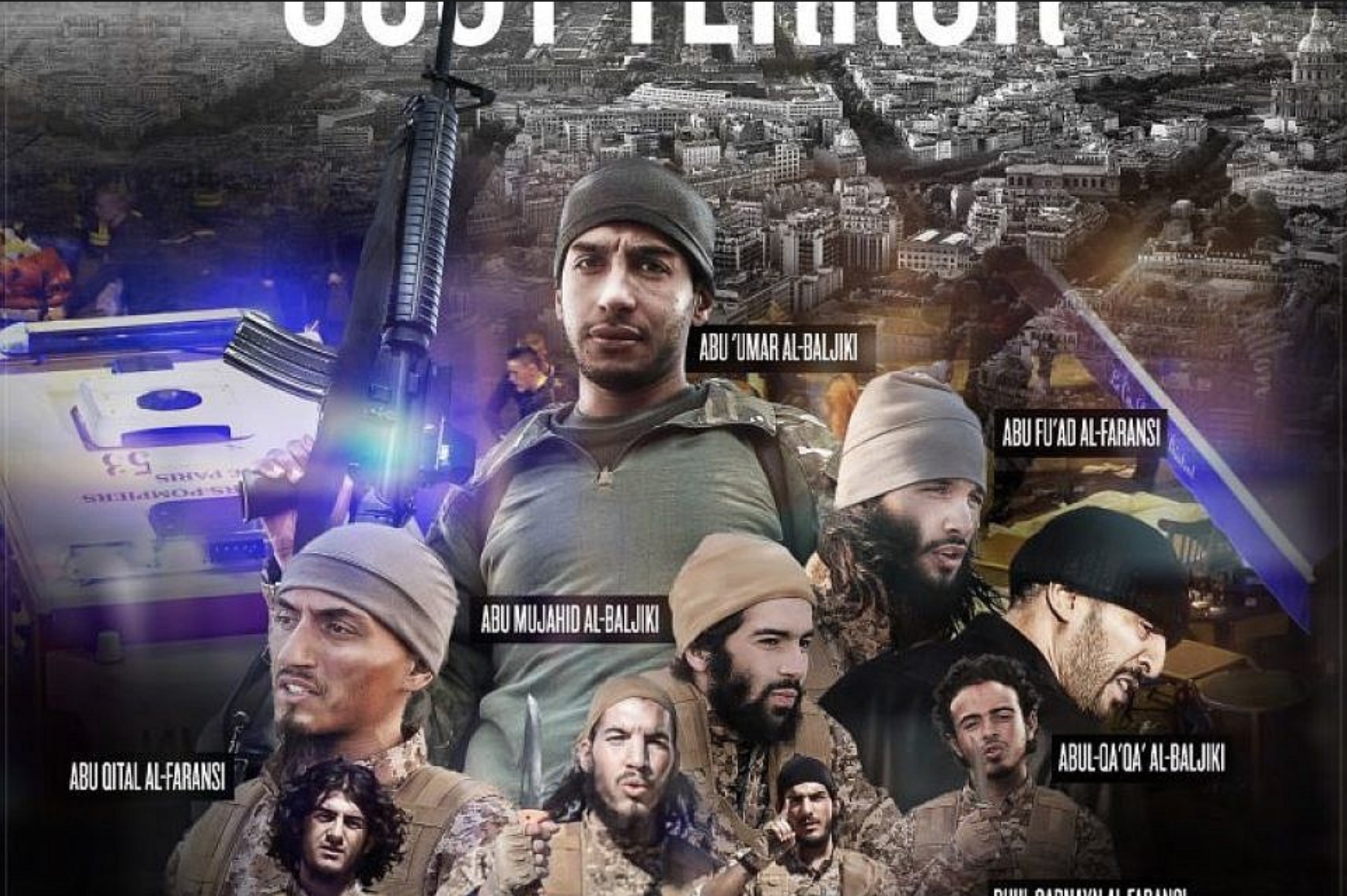

Somewhere along the line Abdelhamid Abaaoud, not an educated man, conflated the myth of the Afghan Jihad with reality. This conflation had disastrous consequences. Abaaoud and his friends joined a jihadist battalion in Syria with delusions of grandeur. Sporting the Afghan Pakhool, he sought to emulate the Afghan Arabs who, he believed, had expelled the Russians from Afghanistan and established Islam before the West and their treacherous allies, known as the ‘Northern Alliance’, came along and destabilised it with democracy. And so when he saw Syrians calling for the same, he dragged their heads along the ground, tied to his American dodge, chortled as his friends denounced the murdered Syrian villagers as apostates and infidels and finally, in a macabre swan song, he painted Paris red in the 2015 terror attack meeting his end in a shoot out in a Saint-Denis flat.

Of course, if Abaaoud knew the history of the Afghan Jihad, perhaps he might have been more critical of the demagogues, sophists and ideologues that peddled the myth right in his backyard in Brussels. But he didn’t, and so him and his friends ‘studied’ texts such as The Great Divider of the Times, a text dealing with the evils of social media and mobiles. There was The Return of Jahiliyyah and 44 Ways to Participate in Jihad. These texts were written by unknowns such as Frere Yahya the Frenchman, brother Yahya al-Faransi, and published by Ansar al-Haqq, the Helpers of the Truth. There were the standard sermons from the internet by Anwar al-Awlaki and biographies of Osama bin Laden that no academic or religious cleric worth his salt would go near, but Abaaoud did. The internet was a great but terrible leveller.

But let’s not blame the internet; the petty criminal became devout in prison and hooked up with Khalid Zerkani, a larger than life Vautrin-like character who was allegedly an Afghan veteran. Zerkani saw himself as a prophet, he exhorted, indoctrinated and encouraged the youth to pursue the jihad. He sanctioned their criminality as godly work; and they robbed, stole and defrauded in the path of God. Zerkani espoused the logic articulated by the then London based jihadi scholar Abu Qatada: to weaken the infidel was permissible and not an immoral act. However Abu Qatada believed it was contrary to the Muslim community’s interest in the West, whereas Zerkani didn’t. So his group, like many of Qatada’s adherents, pursued a life of criminality in the early noughties because they lived in the land of war and infidelity. Whilst Abu Qatada had no connections to Zerkani whatsoever, many of Zerkani’s friends were the scholar’s students. One such student was Seifullah ben Hassine, also known as Abu Iyad al-Tunisi, who had also travelled to Afghanistan in the early noughties. He eventually became the founder of Tunisian Combatant Group, the Tunisian equivalent of the GIA, the extremist group that committed awful atrocities during the Algerian Civil War. Later during the Arab Spring, Hassine went on to found Tunisia’s Ansar al-Shariah and was killed in an air strike in Libya 2015. There were others, like Hassine’s friend Tarek Maaroufi, who distributed his magazine, al-Ansar, in Brussels spreading the jihadi message where the reader could savour op-eds and communiques by Zawahiri and Algerian GIA leaders to the Belgian North African community. We don’t know exactly what the impact was on Abaaoud, but it certainly created a milieu where Abd al-Sattar Dahmane, the assassin of the Afghan leader Ahmed Shah Massoud, and an al-Qaeda operative could hold exhibitions in Brussels about the glories of the Afghan Jihad. Never mind the fact that it was Massoud who fought off nine different Russian campaigns. His wife, Ms. Malika El Aroud and her friend Fatima Aberkane later became fervent recruiters of jihad and were both associates of Zerkani. For Abaaoud, Afghanistan became the mood music for fighting in Syria. Afghanistan was the first truly successful holy war for a generation.

But here’s the thing: perhaps it wasn’t just Abaaoud who amalgamated the myth of Afghan Jihad with reality. Perhaps Zerkani, Hassine and others like Nizar Trabelsi, who went to Afghanistan as they do today in Syria, thought that they were taking part in a divinely sanctioned jihad when they were in fact taking part in a grubby civil war between two warring Islamist factions led by two veterans of the Afghan Jihad, namely Ahmed Shah Massoud and Mullah Omar. After all, the jihad had ended when the Soviets had left in 1989 and Kabul had fallen in 1992, so what were they doing there in the early noughties? These men attended camps run by Afghans, Pakistani intelligence services and al-Qaeda and returned as Afghan ‘veterans’. On to the streets of Brussels and London youngsters like Abaaoud were awestruck by them, believing them to be the living embodiment of the heroes of yore, mujahideen, when they were actually bit players in a bloody war which had resulted in millions of deaths. Sounds awfully familiar, doesn’t it?

Even Jihadi John’s macabre beheadings were nothing unique. Those who grew up in the early noughties know that one of the very first videos going ‘viral’ amongst jihadists was the beheading of a Russian soldier in Chechnya who had allegedly killed and raped Chechen women. This was uploaded on many jihadi websites and forums which had appropriated the symbols of the Afghan jihad and conflated them with something they were not: global jihad. I know from my own research to the book, To The Mountains: My Life in Jihad from Algeria to Afghanistan, that Jihadi John and his friends were aware of this video and greeted each other by sneaking up from behind and slicing their throat with the hand. By the late nineties and early noughties the Afghan Jihad had become the foundational myth for global jihadists.

This conflation of the Afghan myth played itself out in other conflicts, too. So much so that many Muslims did not notice the ugly side of Muslim militancy in Bosnia, Chechnya, Somalia and so forth. Take for instance Bosnia, speak to those who survived the siege of Sarajevo: they do not necessarily have the same flowery picture that Western Muslims have of the foreign fighters going to help them during the conflict in the nineties. UN court documents certainly accuse them of sexual violence and torture. These fighters saw themselves as outside of military discipline and not immune to those crimes that the Serbs were accused of committing. It is no wonder veteran reporter Chris Hedges writes in War is a Force that Gives us Meaning that he preferred a murderous Roman army to an undisciplined militia that is so dependent on the good will of the commander.

The warning signs were missed, what was rejected in the Afghan Jihad became accepted in the Syrian conflict. The medieval practice of taking slave girls was rejected in the Afghan Jihad but accepted amongst Jihadis in Sinjar, 2014 and enforced on the Yazidi community. Similarly, during the Afghan conflict there were several men who claimed caliphood: one of them was based in Lisson Green, London, the other as Olivier Roy notes, replaced the fine mosques with cement cubes and “Saudi-style minarets”. So why should it be so absurd that Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi claimed it on the pulpit of Mosul in 2014? The only reason it appears surprising is because we have not explored that period in depth. It has meant that the likes of Zerkani, who prayed on young men in our communities, could flourish.

If we did explore, we would ask ourselves why for instance so many Jihadi figures became pillars of the jihadi movement in the Muslim world? In what ways did these men become authorities? Since when did participating in fighting turn you into a religious authority? This was the case of Abu Musab al-Zarqawi, the barely literate Iraqi militant who wrote fatwas, or Osama bin Laden whose fighting experience was no longer than a year at best. What and who gave them the religious authority to issue legal edicts? Olivier Roy, an academic with extensive experience in Afghanistan and the mujahideen notes in Jihad and Death, the Global Appeal of Islamic State:

“It is important to realise that this jihadi model is not necessarily terrorist. I was in close contact with international jihadis who came to Afghanistan in the 1980s and who were organised in the “service bureau” that later became al-Qaeda after Abdullah Azzam was murdered in November 1989. Under Azzam’s leadership they never resorted to terrorism, or even suicide bombings (even if they volunteered for the front lines). They never targeted Soviet diplomats or civilians even though these were present in the Arab world. Certainly they had Salafi leanings and readily lectured Afghans about “the right Islam” even if Azzam gave strict instructions in Join the Caravan not to interfere in Afghan society.”

And so by the time we started to question those assumptions, we had already experienced the trauma of an unjustifiable assault on Muslim countries, we were cowed by the cruelty of Guantanamo, the chilling effect of state scrutiny and being fingered as a ‘coconut’ or a ‘house Muslim’ by self-righteous activists who basked in the rays of their own goodness, and so we continued to forget.

An exploration of the Afghan Jihad is essential to understand why we are still looking at a hotel in Nairobi being assaulted by al-Shabaab militants, another organisation that claims its genesis from Afghanistan. We need to read the testimonies of those who participated, not just that of Abdullah Anas and others, but also Afghans veterans like Masood Khalili. And then we should look at the works of academics like the Roys and Heghammer’s of this world who may offer different perspectives that challenge our own notions of the past. Failure to do so could mean that the Abaaouds of the past may haunt us in the near the future.