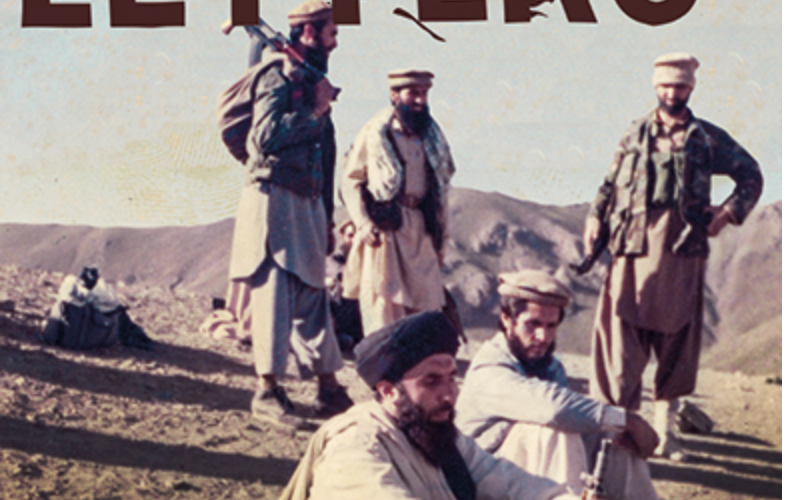

Night Letters: Gulbuddin Hekmatyar and the Afghan Islamists who Changed the World- Book Review

When Kabul fell in 1992, Abdullah Anas recalls in his memoirs, To The Mountain: My Life in Jihad from Algeria to Afghanistan, that he encouraged Osama bin Laden to join him on their victory parade to Kabul. After all, it had been a long struggle, over a decade in fact, for the Soviet-backed Communist government in Kabul to fall.

You would have thought Bin Laden would have jumped at the opportunity, the future al-Qaeda leader had lost friends and spent plenty of treasure to realise this goal, and yet he hesitated.

Rather than savouring victory, his most important concern it seemed, was not to alienate Gulbuddin Hekmatyar, the Hezb-i-Islami leader, one of the main Mujahideen leaders fighting to expel the Soviets.

But ever since the Soviet invasion in 1979, the jihad had been dogged by factional infighting and it continued even as Kabul tottered in defeat. Hekmatyar, who supported many of the Afghan Arabs fighters, would not participate in the triumph orchestrated by his rival Ahmed Shah Massoud and so Bin Laden could not afford to alienate the former.

What Anas touches on fleetingly, Chris Sands and Fazelminallah Qazizai explores with a critical eye in Night Letters: Gulbuddin Hekmatyar and the Afghan Islamist who Changed the World (Hurst) 2019.

It is an immensely impressive piece of research that will no doubt be required reading for journalists, academics and Afghanophiles. Sands and Qazizai have untangled the mindbogglingly messy politics and made sense of the shifting alliances of the Mujahideen factions as they were fighting the Communists.

This biography of Hekmatyar brings Sand’s literary skills and nearly a decade of journalism in Afghanistan with Qazizai’s in-depth knowledge of Afghanistan, connections and understanding of Islamic law to produce an intriguing book.

They bring together three hundred interviews conducted over six years travelling the length and breadth of this most enchanting country to produce a history where no one comes out unscathed.

But out of all the figures that the book touches on from Massoud, Azzam, Rabbani, Bin Laden, Zarqawi, all has passed, and yet Hekmatyar has survived, ran presidential elections and even received a copy of the book!

The book charts the rise of Hekmatyar, an obscure student with little religious training, thrashing it out with the Communists at Kabul university campus to become one of the most charismatic leaders of the Islamic world in the 80s and 90s.

It is a remarkable feat that a man with no religious credentials had the organisational ability, charisma, drive and sheer ruthlessness to not only defeat the Soviets but, as the two authors suggest, plant the seeds for Global Jihadism which traditionally is attributed to Abdullah Azzam – the latter plays only a bit part in the book.

Rather, the authors argue that many of the world’s future jihadists modelled their behaviour on his organisation and extremism. Whether this is a convincing argument, remains to be seen, however, they present plenty of circumstantial evidence which they have fact checked by travelling to those villages and interviewing the relevant people.

The authors argue that many of the world’s future jihadists modelled their behaviour on his organisation and extremism. They show Hekmatyar’s men supporting Azerbaijan in their conflict with Armenia. They show that his language and rhetoric isn’t too far off that of any modern extremists groups now. They allege that he was a fixer and organiser for Osama bin Laden and Zawahiri whilst in exile in Iran.

They also claim that Hekmatyar must have known about the 9/11 attacks and seemed to encourage it whilst Massoud warned against it. After 9/11 it was his men who sheltered the founders of al-Qaeda following the US invasion and helped move the prominent al-Qaeda figures into Iran.

In fact, Hekmatyar personally went to see the late Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein to sound him out on a safe haven for Bin Laden to deal with the repercussions of 9/11 but he was rebuffed.

Moreover the authors show that many men who became involved in terrorism fought in his ranks, for instance, Muhammed Haydar Zammar, the al-Qaeda recruiter and Islamic State group [IS] fighter involved in the 9/11 attacks.

According to the authors, he is described as a mentor and father figure for a former thug-turned ‘good’ Abu Mus’ab Zarqawi – who he palmed off to Ansar al-Islam based on the Iraqi-Iranian border inaugurating the beginnings of al-Qaeda in Iraq.

There are some connections that appear less convincing, but those assertions are cited. For instance, citing Will McCants, they assert that Abu Bakr Naji, the author of the Management of Savagery so lauded by IS, fought in his ranks and what is more, credits Hekmatyar as deepening his understanding of war.

Now, whether he really was the driving force in the Global Jihad movement still needs more exploration, but as Sands told me, this is exactly the point of the book, Hekmatyar’s finger prints are everywhere, enough to warrant further research.

Perhaps it would have been better had they incorporated more Arabic sources into their bulky tome, but considering that it took the authors six years to research and write the book, perhaps it was for the best.

What is certain though is that Hekmatyar’s influence on the Global Jihad can no longer be ignored and the authors should be congratulated for their contribution.

This book review was first published in The New Arab