Into the Heart of Darkness: Working Notes on Three ISIS Jihadists.

Raqqah has fallen. There are many jihadists who will look at this loss with a sense of bitterness. Some foreign fighters are pragmatic. Is the Jihad over? “It goes on” they say, “till the Day of Judgment.” For some though the fall of Raqqah isn’t good news. From the earth shattering moment when Sykes-Picot was broken and men dreamed of reshaping the Middle East in their own image, the nation state reasserted itself. Ironically, what had once been denounced as artificial borders designed by a French and Englishman was re-established with much blood and coin. Foreign fighters, once hailed as ‘heroes’, are now waiting for the day when they will be hounded out of Syria. And some are no doubt preparing for it.

In doing so, some of these fighters are again couching their fate in semi-Romantic terms. These ‘righteous’ ‘pure’ fighters, this Sunni vanguard, stabbed in the back by the ‘apostate’ Syrian SDF who serve only their foreign masters. That at least, is the sense you get when listening to Abu Adam al-Britani’s desperate audio message. He stresses, and no doubt touches a chord, that he abandoned his Porche for a grizzly end in Raqqah and yet, just like the Prophet’s Companions, he would not change his situation for all the world and what is in it.

There is of course no reflection that this bloody mess they are in is their own doing. They like Bin Laden, had gone to save the Ummah but it resulted instead in the loss of thousands of souls. None, in comparison to the Assad regime, but the consequences and reverberations are felt from London to Burma. Like true followers of Bin Laden, they were willing to sacrifice the Ummah for their vision. Bin Laden knew very well that the US response would be overwhelming when he targeted the Twin Towers. His own mufti, Abu Hafs al-Mauritani, resigned in protest and yet Bin Laden, this guest of the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan, was willing to let his Taliban hosts find out on TV that the buildings had fallen. He had no issue with the mass murder of three thousand American souls, and neither did he lose sleep over the loss of thousands upon thousands of Afghan Muslims who would feel the American response. The price was worth paying if it galvanised the Muslim world to wake up from its slumber.

And then when they faced defeat, and they were carted off to Guantanamo by the Americans, these same people accused the Afghans for selling them out. They were unable to grasp that they had sold out the Afghans and, indeed, the Ummah by putting their ideas above anything. ISIS appears to have done the same thing, they provoked the wrath of the international community to such an extent that they were abandoned by their own people. What had started off as a cause of an oppressed people and understood by all and sundry all over the world, irrespective of creed or religion, had been destroyed by Salafi-Jihadis which no doubt was encouraged by the regime. It put the world in a dilemma. Terrible things were happening in Syria for sure, but who did one prefer? Assad, a brutal tyrant with whom one had dealings with over decades- an unpleasant actor but with a discernible modus operandi or an unknown quantity that blows up towers for starters. In Realpolitik, the choice was really not much of a choice and it came at the expense of innocent civilians.

But amidst the rubble of Raqqah, Ibrahim Hussein or Abu Ishāq, as he is known, mans his Doschka, his once chubby cheeks sunken, his Afro is grey with dust. He is grizzled and angry. Perhaps he is unaware that his dream is gone, and all that is left is folly. But he is young, no more than twenty-two and he has that magic which Joseph Conrad describes as the ‘glamour of youth’. He holds a jagged blade, points his finger threateningly at the camera and tells a man described by ISIS as the ‘Pharaoh of the times’:

“Donald Trump, you might have your eyes on Mosul and Raqqah but we have our eyes on Constantinople and Rome with the permission of God, with the permission of God, [sic] we will slaughter you in your own houses, we’ll see.”

Ibrahim uses common Islamic apocalyptic tropes; in the Last Days, it is said that Muslims will conquer both Rome and Constantinople. Ibrahim then returns to his Doschka and fires a round, accompanied by the shout of ‘God is Most Great’. But even he must realise that with Raqqah’s fall he has tasted what Conrad describes as the first pangs of time, “more cruel, more pitiless, more bitter than the sea.”

What follows is a rumination on three young British Muslims, Ibrahim Hussein, Zubair Nur, Gezim Klokoci who travelled to the East to join ISIS and their respective fates. One suspects that they shared, like many young men have done and will do, that “feeling” Joseph Conrad writes about in Youth, that one:

“could last for ever, outlast the sea, the earth, and all men; the deceitful feeling that lures us on to joys, to perils, to love, to vain effort – to death; the triumphant conviction of strength, the heat of life in the handful of dust, the glow in the heart that with every year grows dim, grows cold, grows small, and expires – and expires, too soon, too soon – before life itself.”

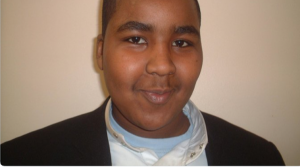

Voyage to the East

Before he left for the East, Ibrahim Hussein was from an unremarkable Somali-British family. Ibrahim grew up on a rough looking council estate in Woolwich, the sort of estate where young roughnecks walk around with cheap Alcatel phones- a tell tale sign of drugs on the estate. If you look close enough, its manifestations are everywhere; in young men waiting on the corner, ready to jump on a cab to deliver ‘something’. If you take pictures, they ask you why you are doing that, as if they were afraid of undercover police. Young men gaunt and pallid walk past, with teeth prematurely decayed. It is unsurprising that one of the neighbours claim that no less than five Somali Brits have left for the East, finding no purpose on this mash-up estate. He claims they were former troublemakers and drug dealers; they left that lifestyle embarking on some modern day Byronic adventure to the East.

Despite limited prospects on the estate, Ibrahim’s father worked hard in IT, and ensured that his son didn’t get swallowed up by it: he paid for his schooling and Ibrahim attended a faith school, London East Academy (LEA). His father no doubt hoped, as many Muslim fathers do, that their offspring do their duty to God, that they are righteous, look after their own and when they are no more, these sons and daughters raise their hands offering prayers on their souls. Whilst Ibrahim was at LEA, he kept himself out of trouble. He wasn’t a great intellect in his class but he flourished. His friends describe him as popular, a gentle big bear, an alpha male and eloquent. Quietly charismatic, he had a way of leading his crew of Somalis in school. As a friend recalled, whenever the Somali kids got up to mischief, Ibrahim almost certainly had something to do with it, and yet you couldn’t quite pin the finger of blame on him.

It was of course there, at LEA, that he met his travelling companion Zubair Nur. He was from a similar background: both his parents were professionals. But the presence of his father was not a constant. His parents had split up and his father worked in the petroleum industry in Qatar. Though Zubair was more devout and knowledgable in terms of religion, that did not translate into leadership. In fact, he was seen as someone needy, insecure and looked up to Ibrahim who took him under his wing.

Both boys left school with more than five A-Cs, but Ibrahim for some reason did not continue his education. Zubair went on to Sixth Form, attending Chelsea Academy where he excelled; he became a school prefect and harboured ambitions for a medical career. When that dream was thwarted due to inadequate grades, he decided to follow in his father’s footsteps, earning himself a place at Royal Holloway University. Zubair wanted to make a lot of money and eventually return to Somalia to develop the country’s infrastructure.

Whilst Zubair had clear direction, for Ibrahim this was a period of aimlessness and he found purpose in Syria. As one of his friends told me, every living thing has a purpose, and Ibrahim found his purpose in ISIS. When you have nothing to do as Ibrahim clearly did, and something as powerful as the image of Sykes-Picot is being shattered, and a caliphate is declared, that is powerful on the Muslim imagination. As one ISIS member, Shabazz Suleman, told Sky news, “the Caliphate is like a magnet”. Arguably, even more so on an impressionable young man. Ibrahim went from the Grime scene to religious devotion and somewhere along the line simple devotion turned to extremism. Part of that is reacting to events around him, part of it because he did not know who he was. His social media footprint however, alluded to more than just politicisation. As his class mate told me, all British Muslim youth are politicised to a degree. They feel a deep sense of injustice when it comes to British foreign policy. The Israeli-Palestinian conflict, the Iraq invasion and other conflicts is an inescapable fact of growing up Muslim in the UK. These young men more than ever have a strong sense of belonging to an Ummah, a trans-national faith community, in the way that many first generation Muslim immigrants to the UK did not. However, these young men were the sons of many identities that often remained unresolved within themselves. To use Oedipus Rex as an example, it is the fact that Oedipus did not know who he was which led to him commit an abominable act. And I would argue that with these young men, whilst their fathers knew who they were, these sons of East and West were still looking. Not knowing who you are in civil society is not a problem; in war it can lead to catastrophe.

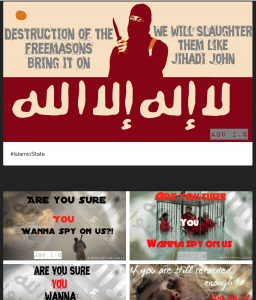

Whilst many in the heady days of 90s Londonistan came across the concept of caliphate at university campuses, Zubair Nur was already well versed in the religious evidences that necessitate a caliphate in secondary school, according to a friend. That’s astonishing and sophisticated. This was well beyond just stories of Khaled bin al-Walid and martial tales of glory and chivalry told to children. Ibrahim’s awareness seemed to start much later, but especially after Syria broke out, the content he posted was extreme. His Tumbler page starts with the corpse of Aylan Kurdi, the young boy washed up on the shores of Turkey, and then followed by a series of posts of Jihadi John playing on the theme of decapitation and Freemasonry. On his twitter feed too, there is increasing evidence of contact with the Portsmouth group, as well as figures associated with Anjem Choudary or al-Muhajiroun. The content got so extreme that his friends felt the need to disassociate themselves from him.

It was interesting that none of his friends informed counter-terror police nor did they notify the relevant authorities. When asked why, one of his friends stood by his decision. Even though he had let him down as a friend, and should have talked him out of it, calling counter-terror police would have had a negative impact on his community. Even if untrue, the friend believed and still does, that him and his friends are on a watch-list and are monitored by the security services. They have a fear that their school, their mosques and other institutions would be shut down and the Media would tear them apart. He was more upset at Ibrahim for revealing his identity and bringing suffering on his family and attention on themselves rather than anything else. Terror laws, it seems, are having a counter-productive effect. The response is not unique to the UK Muslim community as an Irish colleague pointed out, this is exactly the same behaviour he witnessed amongst Catholic boys during the Troubles in Northern Ireland.

Whilst Ibrahim was going one way, Zubair was seen to go to the other. According to his friends, he was ‘free-mixing’, that is, he was hanging out with the opposite sex socially, something that conservative Muslims in general disprove of. Zubair was uploading party pics and showed no sympathy to ISIS; one of his friends even cited a hadith that Zubair had mentioned to show his dislike for ISIS.

“There will arise at the end of time, people who would be young and immature in thought but they would talk in such a manner as if their words are the best among creatures. They will recite the Quran, but it would not go beyond their throats.”

The point is, Zubair was clearly aware of these Prophetic traditions and yet he still left for the East. I can only explain his departure to the love of adventure and the fact that the very word ‘caliphate’ has near mystical connotations in the Muslim consciousness. It is as if the very existence of this political entity, is a Cure All to decades of humiliation suffered at the hands of the colonial powers. This strand of thought has been developed during the 70s and 80s. The tradition of the Abbasid Caliph al-Mu’tasim for instance, preparing an army to protect the honour of Muslim women is often cited as evidence of why Muslims need a caliph.

Accounts suggests that Zubair was also enticed to go by Ibrahim. The latter, it seems, had thought about his journey, and before leaving he messaged his school mates saying “Pray that I get paradise”. He was never seen again.

Ibrahim, Zubair and Gezim travelled together to Syria but what happened next is a bit harder to interpret. Zubair and Ibrahim were far more careful about their security

and rarely posted much about their activities. But Gezim, the youngest of the three, was prolific in his social media activity. It is he who gives us a clue into their doings. He discarded the idea that ‘virtuous’ deeds should be known to no one but God alone: Gezim advertised all his deeds, the good, the bad and the moronic. Arguably, even his good deeds appeared to smack of spiritual arrogance. Clearly Gezim saw himself as a league apart from those who stayed behind in the UK. As he posted: ‘For some, Jihad is an upbeat nasheed in the car’. It was this that gave him license to proselytise, teach people about creed, impose his views and generally school his followers about what Jihad really is, even though he had no qualifications whatsoever apart from having made hijra and fighting.

The Media picked up on these themes and described Gezim or Abu Waqqas al-Albani, as ‘Jihadi Jackass’, after the MTV reality show that showcased all kinds of infantile behaviour by grown men. Gezim, a Brit of Albanian descent, is described as a high school drop out, dimwitted, narcissistic and into conspiracy theories of the Illuminati kind. He also doesn’t seem like the sort of kid that Zubair would mix with. However, from my own investigations, it seems that Gezim met Zubair through a tuition centre. Gezim had recently become devout and sold perfumes to make some extra change. Gezim’s religious knowledge was minimal, as is evidenced by him quoting Abu Hamid al-Ghazali or Algazel, in one of his Instagram posts, unaware that Salafi-Jihadi scholars considered this Medieval theologian as a deviant due to his Sufism.

Nevertheless, what Gezim’s posts reveal is how quickly these boys changed once they entered and grew accustomed to this proto-state. Some things, as this author has experienced, would have been well ordered and other things just as chaotic as other parts of the Middle East, mixed in with the horror of war.

One thing for sure though, many of the rules one adheres to in civilised life began to gradually erode. It happens to all men, as William Golding’s Lord of the Flies so beautifully illustrates. When the journalist Henry Morton Stanley left behind his rear guard, as he continued on to map the African continent, these men committed unspeakable crimes: they became monsters, they enslaved, raped, punished and even fed one of their victims to cannibals whilst making sketches of the ritual. What made these human beings, who would behave quite normally in the smoking rooms of London, behave in such a way? First time in a war zone, you duck every time a car door shuts, later on you joke about it. You see this erosion of civility in Gezim’s posts. You need a lot of moral fibre to keep things together. The is why Chris Hedges, a veteran war correspondent, prefers the discipline of an army than that of a militia. An army may be brutal but subject to institutionalised discipline a militia depends on the abilities and moral character of its commander.

To these young men war became normal; they interspersed their guard duty with trips to the cafe for chocolate ice cream, computer games and plunging into the Euphrates. The permanent presence of war entered the very air they breathed; normal rules of society didn’t apply. You accept things you wouldn’t normally do: walk past the dead, the suffering and the wretched, and even manage to play on the Playstation. And yet, you live intensely and you might even look back at those things with fondness, as time passes. Here, amongst the fighters, the same morbid humour you find amongst some British squaddies or Celtic warriors of centuries past reigns. War bears its imprint on the soul, no matter what age one lives in- and sometimes when you have lived in it for so long, you cannot live without it. Perhaps war itself gives its own sense of meaning, as Chris Hedges has suggested in War is force that gives us meaning.

Ibrahim or Abu Ishāq turns up occasionally in Gezim’s posts: he’s still dropping a few bars of Grime, except now it’s all about Baghdadi and the caliphate. Gezim also posts a video that purports to be from Mosul, a days drive from Raqqah. We see little of Zubair: it is believed that he worked in Mosul working in money transfers before dying in an air strike, but this has not been fully confirmed. His friend’s death does not stop Gezim from continuing with the banter. He earned the epithet ‘Jihadi Jackass’ because he throws down a suicide vest down the stairs; he recites Quran and uploads it to Instagram, he celebrates the terror attacks in Brussels and threatens Heathrow and Gatwick, little realising that this ‘jihad’ of his appears like something out of Four Lions. At some point though, the joke ends for Gezim too: in 2016, as ISIS attempts to retake Palmyra, the Instagram posts stop.

Of the three companions, Ibrahim Hussein remained, and upto now we do not quite know what his fate will be now that Raqqah has fallen. Perhaps, he will be captured and executed by the YPG or SDF, perhaps he will languish in prison. He might slink away into Idlib or to Somalia or remain in the badlands of Deir Zour, where he will hide amongst sympathetic tribes or be hunted by them and eventually return grizzled to the UK.

Whatever happens, dealing with these individuals is paramount for policy makers and will need a lot of resources and time. These men, women and children will have seen and perhaps committed horrible violence which some will never recover from. If they are left to linger in that volatile situation it may manifest itself into more Baghdadis and Adnanis being born, and these men are not unlike Joseph Conrad’s Kurtz from Heart of Darkness. These men will speak of their commitment to Islam but they will perpetrate such terror that will show, like Kurtz, their hollowness.

Working Notes: Gezim Klokoci’s uploads- Life in ISIS Country

Ibrahim Hussein dropping a few bars about the caliphate below.

A foreign fighter makes a prayer for Abu Waqqas and others for martyrdom Raqqah market.

Life in the barracks and activities.

Gezim gives you a tour of his barracks and activities he gets up to.

Gezim’s Quran recitation below.

Frolicking on the Euphrates (below)

The Normalisation of War

Gezim uploads his experiences of war.

Jets above Raqqah here’s an audio clip of an unknown fighter responding to air strikes.

Gezim gives a commentary of jets flying (above). Below Gezim and another foreign fighter boasting about Jihad, Gezim is filming as identified by his voice.

Above Gezim shooting a Glock and enjoying it. Below Gezim is spray painting AK 47 clips

Mosul

NB. Sources have been deliberately anonymised.